As the Top500 celebrates its 30th year, with a $5 VM you too can get into the top 10 ... of 1993

Tan KW

Publish date: Tue, 14 Nov 2023, 11:15 PM

SC23 This year marks the 30th anniversary of the Top500 ranking of the world's publicly known fastest supercomputers.

In celebration of this fact and with the annual Supercomputing event underway in Colerado, we thought it'd be fun, if a bit silly, to see how cheaply we could achieve the performance of a top-ten supercomputer from 1993. So, we spun up a few virtual machines in the cloud and compiled the HPLinpack benchmark. Spoiler alert: you may not be too shocked by this experiment of ours.

At the end of 1993, the fastest supercomputer on record was Fujitsu's Numerical Wind Tunnel, located at Japan's National Aerospace Lab. With a whopping 140 CPU cores, the system managed 124 gigaFLOPS of double-precision (FP64) performance.

Today we have systems breaking the exaFLOPS barrier, but in November 1993, all you needed to do to claim a spot among the 10 most powerful systems was to manage better than the US CM-5/544's 15.1 gigaFLOPs of FP64 performance. So, the target for our cloud virtual machine to beat was 15 gigaFLOPS.

Before we dig into the results, a few notes. We know we could have achieved much, much higher performance if we'd opted for a GPU-enabled instance, however these aren't exactly cheap to rent in the cloud, and GPUs didn't really start appearing in Top500 supercomputers until the mid to late 2000s. It's also much simpler to get Linpack running on a CPU than on a GPU.

These tests were run for the novelty of it, to mark the 30th anniversary, and are by no means scientific or exhaustive.

A $5 cloud VM versus a 30-year-old Top500 super?

But before we could get to testing, we needed to spin up a couple VPCs. For this run we opted to run Linpack in Vultr but this would just as well in AWS, Google Cloud, Azure, Digital Ocean, or whatever cloud provider you prefer.

To start off, we spun up a $5/mo virtual machine instance with a single shared vCPU, 1GB of RAM and a 25GB of storage. With that out of the way, it was time to compile Linpack.

This is where things can get a little complicated since there's actually a fair bit of tweaking and optimization that can be done to eke out a few extra FLOPS. However, for the purposes of this test and in the interest of keeping things as simple as possible, we opted for this guide here. That documentation was written for Ubuntu 18.04 though we found it worked just fine in 20.04 LTS.

To generate our HPL.dat file we used this nifty form that automatically generates an optimized configuration for a Linpack run.

We ran the benchmark three times for a few different VM types and selected the highest score from each run. Here are our findings:

As you can see, our totally unscientific test results showed a single shared vCPU compares quite favorably to November 1993's ten most power supers.

A single CPU thread netted us 31.21 gigaFLOPS of FP64 performance, putting our VM in contention for the number-three ranked supercomputer in 1993, the Minnesota Supercomputing Center's 30.4 gigaFLOPS CM-5/554 Thinking Machines system. Not bad considering that system had 544 SuperSPARC processors while ours had a single CPU thread, albeit running at much higher clock speeds, of course.

As you can see from the chart above, an extra $1/mo saw performance leap to 51.85 gigaFLOPS, while stepping up to an $18 "premium" shared CPU instance with two threads got us closer to 87.46 gigaFLOPS.

However, to beat Fujitsu's Numerical Wind Tunnel required stepping up to a four vCPU VM from which we squeezed 133 gigaFLOPS of FP64 goodness. Unfortunately, jumping up to four threads wasn't nearly as cheap at $48/mo. At that price, Vultr actually sells fractional GPUs which we expect would perform comically better, and will be quite a bit more efficient.

Better options out there

Something we should mention is these were all shared instances, which usually means they've been over provisioned to some degree.

This can lead to unpredictable performance that could vary from run to run depending how heavily loaded the host system is in its cloud region.

In our highly unscientific runs we didn't see much variation. We think this is because the cores just weren't that heavily loaded. Running the same test on a dedicated CPU instance rendered near identical results as our $6/mo instance but at 5x the cost.

But beyond the novelty of this little experiment, there's not really much point. If you need to get your hands on a bunch of FLOPS on short notice, there are plenty of CPU and GPU instances optimized for this kind of work. They won't be anywhere as cheap as a $5/mo instance, but most these are actually billed by the hour so for real-world workloads the actual cost is going to be determined by how quickly you can get the job done.

And never mind how your smartphone compares to these 30-year-old systems.

In any case, The Register will be on the ground in Denver this for SC23 where we'll be bringing you the latest insights into the world of high-performance computing and AI. And for more analysis and commentary, don't forget our pals at The Next Platform, who have the conference covered too. ®

https://www.theregister.com//2023/11/14/five_dollar_supercomputer/

More articles on Future Tech

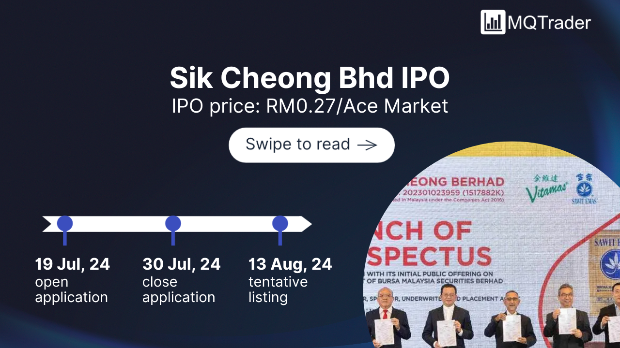

Created by Tan KW | Jul 31, 2024

Created by Tan KW | Jul 31, 2024

Created by Tan KW | Jul 31, 2024