US-China Relations and Wars - Ray Dalio

Tan KW

Publish date: Sat, 26 Sep 2020, 10:53 PM

Preface: In this chapter I will be looking at the positions that the US and China now find themselves in and what being in these positions means for US-China relations. Because the US and China are now rival powers in a number of domains, they are in “conflicts” or “wars” in these domains, so we will be looking at where these stand. Because for the most part what we will be looking at are just new versions of old and classic conflicts (e.g., new technologies in a classic technology war, new weapons in a classic military war, etc.), we will be looking at them in the context of what has happened repeatedly in history and with the timeless and universal principles we learned from studying these cases. While I will be looking at the range of possibilities that one might consider, I will be doing that without getting into what the future might look like. I will do that in “The Future,” the concluding chapter of this book. In this chapter I will also be moving a bit more from just conveying facts to sharing opinions (i.e., sharing my uncertain conjectures).

As with my other chapters if you want to quickly read this chapter you can read just that which is in bold and if you want to read just the principles, you can read that which is in italics.

I will start by passing along three principles of mine about relationships that pertain to all relationships—between people, between organizations, etc.—including the US-China relationship. Like any of my other principles you can take them or leave them as you like. They are just what I have observed to be true and have worked for me. Feel free to skip them if you’re not interested.

My main principle about relationships that I think is relevant to the US-China relationship is:

- Both parties in a relationship can choose whether they will have a win-win cooperative-competitive relationship or a lose-lose mutually threatening relationship, though it takes both of them to agree on what type of relationship they will have. If they choose to have a primarily win-win cooperative-competitive relationship they will take into consideration what is really important to the other and try to give it to them in exchange for them reciprocating. In that type of win-win relationship, they can have tough negotiations done with respect and consideration, competing like two friendly merchants at a bazaar or two friendly teams at the Olympics. If they chose to have a lose-lose mutually threatening relationship they will primarily think about how they can hurt the other in the hope of forcing the other into a position of fear in order to get what they want. In that type of lose-lose relationship they will have more destructive wars than productive exchanges. History has shown that small wars can get beyond anyone’s control and turn into big wars that are much worse than even the leaders who chose this path imagined so that virtually all parties wish that they chose the first path. Either side can force the second path on the other while it takes both sides to follow the first path. In the back of the minds of all parties, regardless of which path they choose, should be their relative powers. In the first case, the parties should realize what the other could force on them and appreciate the quality of the exchange without getting too pushy, while in the second case, the parties should realize that power will be defined by the relative abilities to endure pain as much as the relative abilities to inflict it. When it isn't clear exactly how much power either side has to reward and punish the other, the first path is the safer way because there is great uncertainty around how each side can hurt the other. On the other hand, the second path will certainly make clear which party is dominant and which one will have to be submissive after the hell of war is over. That brings me to my main power principle.

My main principle about power is:

- Have power, respect power, and use power wisely. Having power is good because power will win out over agreements, rules, and laws all the time. That’s because, when push comes to shove, those who have the power either to enforce their interpretation of the rules and laws or to overturn the rules and laws will get what they want. The sequence of using power is as follows. When there are disagreements, the parties disagreeing will first try to resolve them without going to rules/laws by trying to agree on what to do by themselves. If that doesn’t work, they will try using the agreements/rules/laws that they agreed to abide by. If that doesn’t work, those who want to get what they want more than they respect the rules will resort to using their power. When one party resorts to using its power and the other side in the dispute isn’t sufficiently intimidated to knuckle under, there will be a war. A war is the testing of relative power. Wars can be all-out or they can be contained; in either case they will be whatever is required to determine who gets what. A war will typically establish one side’s supremacy and will be followed by a peace because nobody wants to fight the clearly most powerful entity until that entity is no longer clearly the most powerful. At that time, this dynamic will begin again. It is important to respect power because it’s not smart to fight a war that one is going to lose; it is preferable to negotiate the best settlement possible (that is unless one wants to be a martyr, which is usually for stupid ego reasons rather than for sensible strategic reasons). It is also important to use power wisely. Using power wisely doesn’t necessarily mean forcing others to give you what you want—i.e., bullying them. It includes recognizing that generosity and trust are powerful forces for producing win-win relationships, which are fabulously more rewarding than lose-lose relationships. In other words, it is often the case that using one’s “hard powers” is not the best path and that using one’s “soft powers” is preferable.1 If one is in a lose-lose relationship, one has to get out of it one way or another, preferably through separation though possibly through war. To handle one’s power wisely, it’s usually best not to show it because it will usually lead others to feel threatened and build their counter-threatening powers, which will lead to a mutually threatening relationship. Power is usually best handled like a hidden knife that can be brought out in the event of a fight. But there are some times that, when push comes to shove, showing one’s power and threatening to use it is most effective for improving one’s negotiating position and preventing a fight. It is valuable to know what matters to the other party most and least, especially what they will and won’t fight for and how they will fight. That is best discovered by looking at the types of relationships they have had and the ways they used power in the past, by imagining what they are going after, and by testing them through trial and error. Sometimes mutual testing leads to tit-for-tat escalations that dangerously put both parties in the difficult position of having to choose between fighting and being caught bluffing. Escalating tit-for-tat wars often take conflicts beyond where either side would logically want them to go. Knowing where the balance of power lies—i.e., knowing who would gain and lose what in the event of a fight—should always be kept in mind because it is essentially the equilibrium level that parties keep of in the back of their minds when considering what a “fair” resolution of a dispute is—like thinking about what results a court fight would lead to when considering what the terms of a negotiated agreement should be. Though it is generally desirable to have power, it is also desirable to not have powers that one doesn’t need. That is because maintaining power consumes resources, most importantly your time and your money. With power comes the burden of responsibilities. While most people think that having lots of power is best, I have often been struck by how happy less powerful people can be relative to more powerful people. When thinking about how to use power wisely, it’s also important to think about when to reach an agreement and when to fight. To do that, it is important to imagine how one’s power will change over time. It is desirable to use one’s power to negotiate an agreement, enforce an agreement, or fight a war when one’s power is greatest. That means that it pays to fight early if one’s relative power is declining and fight later if it’s rising. Of course there are also times that wars are logical and necessary to keep or get what one needs. That brings me to my main principle about war.

My main principle about war is:

- When two competing entities have comparable powers that include the power to destroy the other, the risks of a war to the death are high unless both parties have extremely high trust that they won’t be unacceptably harmed or killed by the other. Imagine that you are dealing with someone who can either cooperate with you or kill you and that you can either cooperate with them or kill them, and neither of you can be certain what the other will do. What would you do? Even though the best thing for you and your opponent to do is cooperate, the logical thing for each of you to do is to kill the other before being killed by the other. That is because survival is of paramount importance and you don’t know if they will kill you, though you do know that it is in their interest to kill you before you kill them. In game theory being in this position is called the “prisoner’s dilemma.” It is why establishing mutually assured protections against existential harms that the opponents can inflict on each other are necessary to avoid deadly wars. Establishing exchanges of benefits and dependencies that would be intolerable to lose further reinforces good relations. Because a) most wars occur when it isn’t clear which side is most powerful so the outcomes are uncertain, b) the costs of wars are enormous, and c) losing wars is ruinous, they are extremely dangerous and must only be entered into if there is confidence that you will not have unacceptable losses, so you must think hard about what you will really fight to the death for.

While I am primarily focusing on US-China relations in this chapter, the game we and global policy makers are playing is like a multidimensional chess game that requires each player to consider the many positions and possible moves of a number of key players (i.e., countries) that are also playing the game, with each of these players having a wide range of considerations (economic, political, military, etc.) that they have to weigh to make their moves well. For example, the relevant other players that are now in this multidimensional game include Russia, Japan, India, other Asian countries, Australia, and European countries, and all of them have many considerations and constituents that will determine their moves. From playing the game I play—i.e., global macro investing—I know how complicated it is to simultaneously consider all that is relevant in order to make winning decisions. I also know that what I do is not as complicated as what those in the seats of power do and I know that I don’t have access to information that is as good as what they have, so it would be arrogant for me to think I know better than they do about what’s going on and how to best handle it. For those reasons I am offering my views with humility. With that equivocation I will tell you how I see the US-China relationship and the world setting in light of these wars, and I will be brutally honest.

The Positions the Americans and Chinese Are In

As I see it, destiny and the Big Cycle manifestations of it have put these two countries and their leaders in the positions they are now in. They led the United States to go through its mutually reinforcing Big Cycles of successes, which led to excesses that led to weakening in a number of areas. Similarly they led China to go through its Big Cycle declines, which led to intolerably bad conditions that led to revolutionary changes and to the mutually reinforcing upswings that it is now in.

For example, destiny and the big debt cycle led the US to find itself now in the late-cycle phase of the long-term debt cycle in which it has too much debt and needs to rapidly produce much more debt, which it can’t service with hard currency so it has to monetize its debt in the classic late-cycle way of printing money to fund the government’s deficits. Ironically and classically being in this bad position is the consequence of the United States’ successes that led to these excesses. For example, it is because of the United States’ great global successes that the US dollar became the world’s dominant reserve currency, which allowed Americans to borrow excessively from the rest of the world (including from China) which put the US in the tenuous position of owing other countries (including China) a lot of money and which has put these other countries in the tenuous position of holding the debt of an overly indebted country that is rapidly increasing and monetizing its debt and that pays significantly negative real interest rates to those holding it. In other words it is because of the classic reserve currency cycle that China wanted to save a lot in the world’s reserve currency, which led it to lend so much to Americans who wanted to borrow so much, which has put the Chinese and Americans in this awkward big debtor-creditor relationship when these wars are going on between them.

Destiny and the way the wealth cycle works, especially under capitalism, led to the incentives and resources being put into place that led Americans to produce great advances, wealth, and eventually the large wealth gaps that are now causing conflicts, threatening the domestic order, and threatening the productivity that is required for the US to stay strong. In China it was the classic collapse of China’s finances due to debt and money weaknesses, internal conflicts, and conflicts with foreign powers that led to China’s Big Cycle declines at the same time that the US was ascending, and it was the extremity of these terrible conditions that produced the revolutionary changes that eventually led to the creation of incentives and market/capitalist approaches that produced China’s great advances, great wealth, and the large wealth gaps that it is understandably increasingly concerned about.

Similarly destiny and the way the global power cycle works have now put the United States in the unfortunate position of having to choose between a) fighting to defend its position and its existing world order and b) retreating. For example, it is because the United States won the war in the Pacific in World War II that it, rather than any other country, will to have to choose between a) defending Taiwan—a place that most Americans don’t know where in the world it is and can’t spell its name—and b) retreating. It is because of that destiny and that global power cycle that the United States now has military bases in more than 70 countries in order to defend its world order even though it is uneconomical to do so.

History has shown that the successes of all countries depend on sustaining the strengthening forces without producing the excesses that lead to their declines. The really successful ones have been able to do that in a big way for 200-300 years. None has been able to do it forever.

Thus far in this book we looked at the history of the last 500 years focusing especially on the rise and decline cycles of the Dutch, British, and American reserve currency empires and the last 1,400 years of China’s dynasties, which has brought us up to the present. The goal has been to put where we are in the context of the big-picture stories that got us here and to see the cause/effect patterns of how things work so that we can put where we are into better perspective. Now we need to drop down and look at where we are in more detail, hopefully without losing sight of that big picture. As we drop down, imperceptibly small things—TikTok, Huawei, Hong Kong sanctions, closing consulates, moving battleships, unprecedented monetary policies, political fights, social conflicts, and many others—will start to appear much larger, and we will find ourselves in a blizzard of them that comes at us every day. Each warrants more than a chapter-long examination, which I don’t intend to do here, but I will touch on the major issues.

History has taught us that there are five major types of wars—1) trade/economic wars, 2) technology wars, 3) geopolitical wars, 4) capital wars, and 5) military wars—that need to be considered. While all sensible people wish that these “wars” weren’t occurring and that cooperation was occurring in their places, we must be practical in recognizing that they exist, and we should use past cases in history and our understandings of actual developments as they are taking place to think about what is most likely to happen next and how to deal with it well. We see them transpiring in various degrees of play now. They should not be mistaken as individual conflicts but rather recognized as interrelated conflicts that are extensions of one bigger evolving conflict. In watching them transpire we need to observe and try to understand each side’s strategic goals—e.g., are they trying to hasten a conflict (which some Americans think is best for the US because time is on China’s side because China is growing its strengths at a faster pace) or are they trying to ease the conflicts (because they believe that they would be better off if there is no war)? In order to prevent these from escalating out of control, it will be important for leaders of both countries to be clear about what the “red lines” and “trip wires” are that signal changes in the seriousness of the conflict. Let’s now take a look at these wars with the lessons from history and the principles they provide in mind.

The Trade/Economic War

Like all wars, the trade war can go from being a polite dispute to being life-threatening, depending on how far the combatants want to take it.

Thus far we haven’t seen the US-China trade war taken very far—it just includes classic tariffs and import restrictions that are reminiscent of those we have repeatedly seen in other similar periods of conflict (e.g., the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930). We have seen the trade negotiations and what they achieved reflected in a very limited Phase One Trade Agreement that is in its early stages and is being tentatively implemented. As we have seen, this “negotiation” was about testing each other’s powers rather than looking to global laws and judges (like the World Trade Organization) to achieve fair resolution. That—i.e., via tests of power—is how all these wars will be fought. The big question is how far these tests of power will go and what form will they take.

Beyond the trade dispute there are three major economic criticisms the US has about China’s handling of its economy.

- The Chinese government pursues a wide range of evolving interventionist policies and practices aimed at limiting market access for imported goods, services, and businesses, thus protecting its domestic industries by creating unfair practices.

- The Chinese offer significant government guidance, resources, and regulatory support to Chinese industries, most notably including policies designed to extract advanced technologies from foreign companies, particularly in sensitive sectors.

- The Chinese are stealing intellectual property, with some of this stealing believed to be state-sponsored and some of it believed to be outside the government’s direct control.

Generally speaking the United States has responded to these things both by trying to alter what the Chinese are doing (e.g., to get them to open their markets to Americans) and by doing its own versions of these things (closing American markets to the Chinese). Americans won’t admit to doing some of the things they are doing (e.g., taking intellectual property) any more than the Chinese will admit doing them because the public relations’ costs of admitting to doing them are too great. When they are looking for supporters of their causes, all leaders want to appear to be the leaders of the army that is fighting for good against the evil army that is doing bad things. That is why we hear accusations from both sides that the other is doing evil things and no disclosures of the similar things that they are doing. As a principle…

When things are going well it is easy to keep the moral high ground. However, when the fighting gets tough, it becomes easier to justify doing that which was previously considered immoral (though rather than calling it immoral it is called moral). As the fighting becomes tougher a dichotomy emerges between the idealistic descriptions of what is being done (which is good for public relations within the country) and the practical things that are being done to win. That is because in wars leaders want to convince their constituents that “we are good and they are evil” because that is the most effective way to rally people’s support, in some cases to the point that they are willing to kill or die for the cause. Though true, it is not easy to inspire people if a practical leader explains that “there are no laws in war” other than the ethical laws people impose on themselves and “we have to play by the same rules they play by or we will stupidly fight by self-imposing that we do it with one hand behind our backs.”

Regarding the trade war I believe that we have pretty much seen the best trade agreement that we are going to see and that the risks of this war worsening are greater than the likelihood that it will improve, and we won’t see any treaty or tariff changes anytime soon as all trade negotiations are on hold until well after the US presidential elections. Beyond the elections, a lot hinges on who wins and how they will approach this conflict. That will be a big influence on how Americans and the Chinese approach the Big Cycle destinies that are in the process of unfolding. As things now stand, the one thing, maybe the only thing, that both US political parties agree on is being hawkish on China. How hawkish and how exactly that hawkishness is expressed and reacted to by the Chinese are now unknown.

How could this war worsen?

Classically, the most dangerous part of the trade/economic war comes when countries cut the other off from essential imports (e.g., China cutting the US off from rare earth elements that are needed for the production of lots of high-tech items, auto engines, and defense systems, and the US cutting China off from essential technologies) and/or from essential imports from other countries (e.g., the US cutting China off from semiconductors from Taiwan, crude oil from the Middle East or Russia, or metals from Australia)—much like the US cutting off oil to Japan was a short leading indicator of the military war that followed. Thus far we haven’t seen this, though we have seen movements in this direction. I’m not saying such a move is likely but I do want to be clear that moves to cut off essential imports from either side would signal a major escalation that could lead to a much worse conflict. If that doesn’t happen evolution will take its normal course so international balances of payments will evolve primarily based on each country’s evolving competitiveness.

For these reasons both countries, especially China, are shifting to more domestic production and “decoupling.”2 As President Xi has said, the world is “undergoing changes not seen in a century” and “in the current external environment of rising protectionism, downturn in the world economy, and shrinking global markets, [China] must give full play to the advantages of the domestic super-large-scale market.” Over the last 40 years it acquired the abilities to do this. Over the next five years we should see both countries become more independent from each other. Obviously the rate of reducing one’s dependencies that can be cut off will be much greater for China over the next 5-10 years than for the United States.

The Technology War

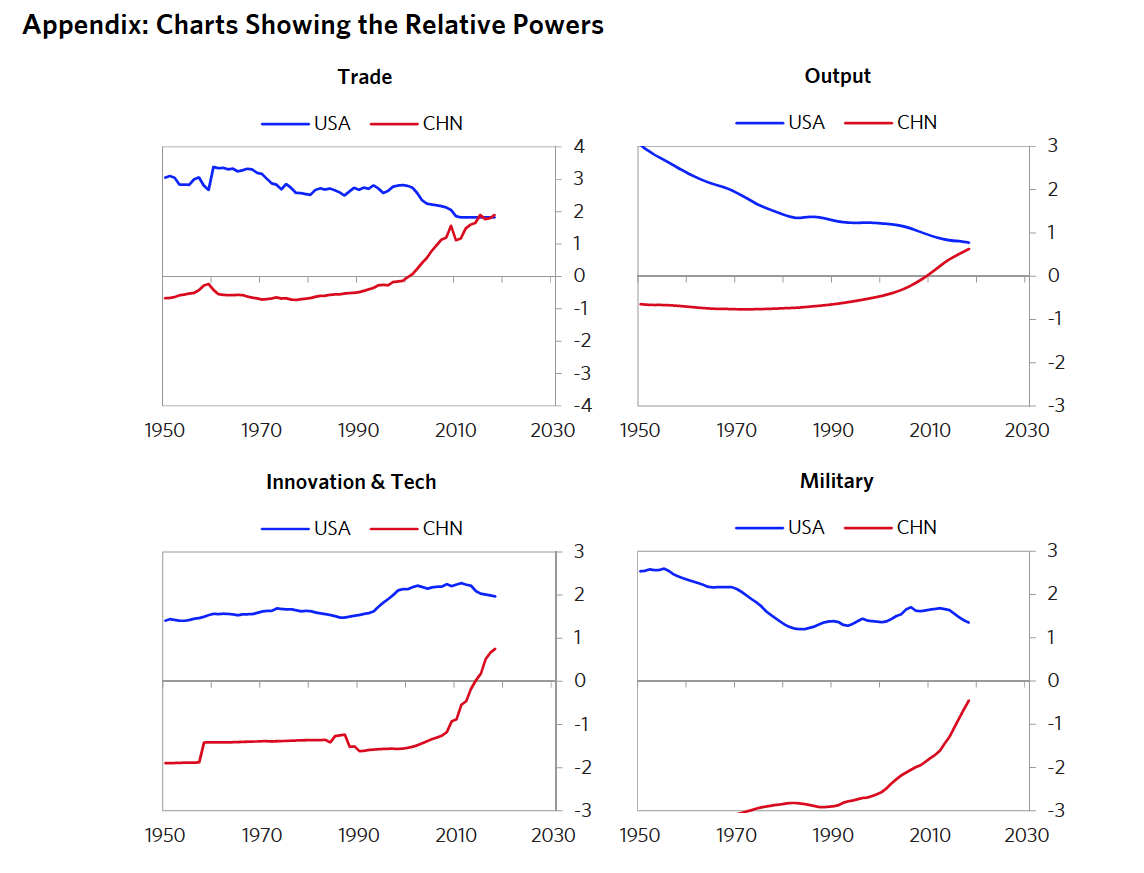

The technology war is a much more serious war than the trade war because whoever wins the technology war will probably also win the economic and military wars.

The US and China are now the dominant players in the world’s big tech sectors and these big tech sectors are the industries of the future. The Chinese tech sector has rapidly developed domestically to serve the Chinese in China and to become a competitor in world markets. At the same time China remains highly dependent on technologies from the United States and other countries (e.g., semiconductor chips from Taiwan). That makes the United States vulnerable to the increased development and competition of Chinese technologies and makes the Chinese vulnerable to being cut off from American or non-American essential technologies.

The United States appears now to have greater technology abilities overall, though it varies by type of technology and the US is losing its lead. For example, while the US is ahead in advanced AI development, it is behind in 5G. As an imperfect reflection of this lead the market capitalizations of US tech companies in total are about twice the size of China’s with China’s share rising faster than America’s share. This calculation understates China’s relative strength because it doesn’t include some of the big private companies (like Huawei and Ant Financial) and the non-company (i.e., government) technology developments, which are larger in China than they are in the United States. Today the largest public Chinese tech companies (Alibaba and Tencent) are already the fifth and seventh largest technology companies in the world, right behind some of the largest US “FAAMG” stocks. Some of the most important technology areas are being led by the Chinese. For example, 40% of the world’s largest civilian supercomputers are now in China, China is leading the 5G race, and it is leading in some dimensions of the AI/big data race and some dimensions of the quantum computing/encryption/communications race. Similar leads in other technologies exist, such as in fintech where the dollar volume of e-commerce transactions and mobile-based payments in China is the highest in the world and well ahead of that in the US. There are of course technologies that I, and even our most informed intelligence services, don’t know about that are being developed in secret.

China will probably advance its technologies and the quality of its decision making that is enabled by them faster than the US will. Big data + big AI + big computing = superior decision making. The Chinese are collecting vastly more data per person than is collected in the US (and they have more than four times as many people) and they are investing heavily in AI and big computing to make the most of it. The amounts of resources that are being poured into these and other technology areas are far greater than in the US. As for providing money, both venture capitalists and the government are providing virtually unlimited amounts to Chinese developers. As for providing people, the numbers of science, technology, engineering, and math students that are coming out of college and pursuing tech careers in China is about eight times that in the US. While the United States has an overall technology lead (though it is behind in some areas) and of course has some big hubs for new innovations especially in its top universities and its big tech companies, so the US isn’t out of the game, its relative position is declining because China’s technological innovation abilities are improving at a faster pace. Remember that China is a country whose leaders 36 years ago marveled at the handheld calculators I gave them, and imagine where they might be 36 years from now, which is not far away.

To fight the technology threats the United States is responding by preventing Chinese companies (like Huawei, TikTok, and WeChat) from being used in the United States, trying to undermine their usage internationally, and possibly hurting their viability through sanctions that prevent them from getting items needed for production. Is the United States doing that because a) China is using these companies to spy in the United States and elsewhere, b) because the United States is worried about them and other Chinese technology companies being more competitive, and/or c) as retaliation for the Chinese not allowing American tech companies to have free access to the Chinese market? While that is debatable, there is no doubt that these and other Chinese companies are becoming more competitive at a fast pace. In response to this competitive threat the United States is moving to contain or kill threatening tech companies. Interestingly, while the United States is cutting off access to intellectual property, it would have had a much greater power to do so not long ago because the United States had so much more intellectual property relative to others. China has started to do the same to the United States, which will increasingly hurt because Chinese IP is becoming better in many ways. They have come a long way in a short time from marveling at cheap calculators.

Regarding the stealing of technologies, while it is generally agreed to be a big threat (1 in 5 North America-based companies in a 2019 CNBC Global CFO Council survey claimed to have had intellectual property stolen by Chinese companies3), it does not fully explain actions taken against Chinese tech companies. If a company is breaking a law within a country (e.g., Huawei in the US) one would expect to see that crime prosecuted legally so one could see the evidence that shows the spying devices embedded within the technologies. We aren’t seeing this. Fear of growing competitiveness is as large or larger a motivator of the attacks on Chinese technology companies, but one can’t expect policy makers to say that. American leaders can’t admit that the competitiveness of US technology is slipping and can’t argue against allowing free competition to the American people, who for ages have been taught to believe that competition is both fair and the best process for producing the best results. As a practical matter stealing intellectual property has been going on for as long as there is recorded history and has always been difficult to prevent. As we saw in earlier chapters the British did it to the Dutch and the Americans did it to the British to make themselves more competitive. “Stealing” implies breaking a law. When the war is between countries there are no laws, judges, or juries to resolve disputes and the real reasons decisions are made aren’t always disclosed by those who are making them. I don’t mean to imply that the reasons behind the United States’ aggressive actions are not good ones; I don’t know if they are. I’m just saying that they might not be exactly as stated. Protectionist policies have long existed to protect companies from foreign competition. Huawei’s technology is certainly threatening because it’s better than American technology. Look at Alibaba and Tencent and compare them with American equivalents. Americans might ask why these companies are not competing in the US. It is mostly for the same reasons that Amazon and a number of other American tech companies aren’t freely competing in China. In any case, there is a tech decoupling going on that is part of the greater decoupling of China and the US, which will have a huge impact on what the world will look like in five years.

What would a worsening of the tech war look like?

Still, the United States has a technology lead (though it’s shrinking fast). As of result, as of now the Chinese have great dependencies on imported technologies from both the US and non-US sources that the US can influence. This creates a great vulnerability for China, which creates a great weapon for the United States. It most obviously exists in advanced semiconductors, though it exists in other technologies as well. The dynamic with the world’s leading chip maker—Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, which provides the Chinese and the world with needed chips and which can be influenced by the United States—is one of many interesting dynamics to watch. There are many such Chinese technology imports that are essential for China’s well-being, and much fewer American imports from China that are essential for the United States’ well-being. If the United States shuts off Chinese access to essential technologies that would signal a major step up in war risks. On the other hand, if events continue to transpire as they have been transpiring, China will be much more independent and in a much stronger position than the United States technologically in 5-10 years, at which time we will see these technologies much more decoupled.

The Geopolitical War

Sovereignty, especially as it relates to the Chinese mainland, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and the East and South China Seas, is probably China’s biggest issue. As you might imagine, the “100 years of humiliation” period and the invasions by foreign “barbarians” during it gave Mao and the Chinese leaders to this day compelling reasons to a) have complete sovereignty within their borders, b) get back the parts of China that were taken away from them (e.g., Taiwan and Hong Kong), and c) never be so weak that they can be pushed around by foreign powers. China’s desire for sovereignty and to maintain its distinct ways of doing things (i.e., its culture) are why the Chinese reject American demands for them to change Chinese internal policies (e.g., to be more democratic, to handle Tibetans and the Uighurs differently, to dictate China’s dealing with Hong Kong and Taiwan, etc.). In private some Chinese point out that they don’t dictate how the United States should treat people within its borders. They also believe that the United States and European countries are culturally prone to proselytizing—i.e., to imposing on others their values, their Judeo-Christian beliefs, their morals, and their ways of operating—and that this inclination developed through the millennia, since before the Crusades. To them the sovereignty risk and the proselytizing risk make a dangerous combination that could threaten China’s ability to be all it can be by following the approaches that it believes are best. The Chinese believe that their having that sovereignty and that ability to approach things that they believe is best as determined by their hierarchical governance structure is uncompromisable. Regarding the sovereignty issue, they also point out that there are reasons for them to believe that the United States would topple their government—i.e., the Chinese Communist Party—if it could, which is also intolerable.4 These are the biggest existential threats that I believe the Chinese would fight to the death to defeat and the United States must be careful in dealing with China if it wants to prevent a hot war. For issues not involving sovereignty, I believe the Chinese expect to fight to influence them non-violently but to avoid having a hot war over.

Probably the most dangerous important sovereignty issue that is difficult to imagine the peaceful resolution of is the Taiwan issue. Many Chinese people believe that the United States will never follow through with its implied promise to allow Taiwan and China to unite unless forced. They point out that when the US sells the Taiwanese F-16s and other weapons systems it sure doesn’t look like the United States is facilitating the stated goal of having the peaceful reunification of China. As a result, they believe that the only way to assure that China is safe and united is to have the power to the oppose the US in the hope that the US will sensibly acquiesce when faced with a greater Chinese power. My understanding is that China is now stronger militarily in that region. Also, China is likely to get militarily stronger at a faster pace. So, as I mentioned earlier, I would worry a lot if we were to see an emerging fight over sovereignty, especially if we were to see a “Fourth Taiwan Strait Crisis.” Would the US fight to defend Taiwan? Uncertain. The US not fighting would be a great geopolitical win for China and a great humiliation for the US. It would signal the decline of the American Empire in the Pacific and beyond in much the same way as the British loss of the Suez Canal signaled the end of the British Empire and beyond. The implications of that would extend well beyond that loss. For example, in the British case it signaled the end of the British pound as a reserve currency. The more of a show the US makes of defending Taiwan the greater the humiliation of a lost war or a retreat would be. That is concerning because the United States has been making quite a show of defending Taiwan while destiny appears to be bringing that closer to a reality. If the US does fight, I believe that a war with China over Taiwan that costs American lives would be very unpopular in the US and the US will probably lose that fight, so the big question is whether that will lead to a broader war. That scares everyone. Hopefully the fear of that great war and the destruction it would produce, like the fear of mutually assured destruction, will prevent it.

At the same time, from my discussions it is my belief that China has a strong desire not to have a hot war with the US or to forcibly control other countries (as distinct from having the desire to be all that it can be and to influence countries within its region). I know that the Chinese leadership knows how terrible a hot war would be and worries about unintentionally slipping into one the way World War I was unintentionally slipped into. They would much prefer a cooperative relationship if such a relationship is possible and, I suspect, they would happily divide the world into different spheres of influence. Still they have their “red lines” (i.e., limits to what can be compromised on that if crossed would lead to a hot war) and they expect more challenging times ahead. For example, as President Xi said in his 2019 New Year’s address, “Looking at the world at large, we are facing a period of major change never seen in a century. No matter what these changes bring, China will remain resolute and confident in its defense of national sovereignty and security.”5

Regarding influence around the world, for both the United States and China there are certain areas that each finds most important, primarily on the basis of proximity (they care most about countries and areas closest to them) and/or obtaining essentials (e.g., they care most about not being cut off from essential minerals and technologies), and to a lesser extent their export markets. The areas that are most important to the Chinese are first those that they consider to be part of China, second those on their borders (e.g., in the China Seas) and those in key supply lanes (e.g., Belt and Road countries) or those that are suppliers of key imports, and third other countries of economic or strategic importance for alliances, in that order.

Over the past few years China has significantly expanded its activities in these strategically important countries, especially Belt and Road countries, resource-rich developing countries, and some developed countries, which is having a greater role in affecting geopolitical relations. These activities are economic and occur via increasing investments in targeted countries (e.g., loans, purchases of assets, building infrastructure facilities such as roads and stadiums, and providing military and other supports to countries’ leaders) while the US is receding from providing to these places. This economic globalization has been so extensive that most countries have had to think hard about their policies regarding allowing the Chinese to buy assets within their borders.

Generally speaking the Chinese appear to want tributary-like relationships with most non-rival countries, though the closer their proximity to China, the greater the influence China wants over them. In reaction to these changing circumstances most countries, in varying degrees, are wrestling with the question of whether it is better to be aligned with the United States or China, with those in closest proximity needing to give the most consideration to this question. In discussions with leaders in different parts of the world I have repeatedly heard it said that there are two overriding considerations—economics and military. They almost all say that if they were to choose on the basis of economics, they would choose China because China is more important to them economically (in trade and capital flows), while if they were to choose on the basis of military support, the United States has the edge but the big question is whether the United States will be there to protect them militarily when they need protection. Most doubt that the US will fight for them, and some in the Asia-Pacific region question whether the US has the power to win if it wanted to.

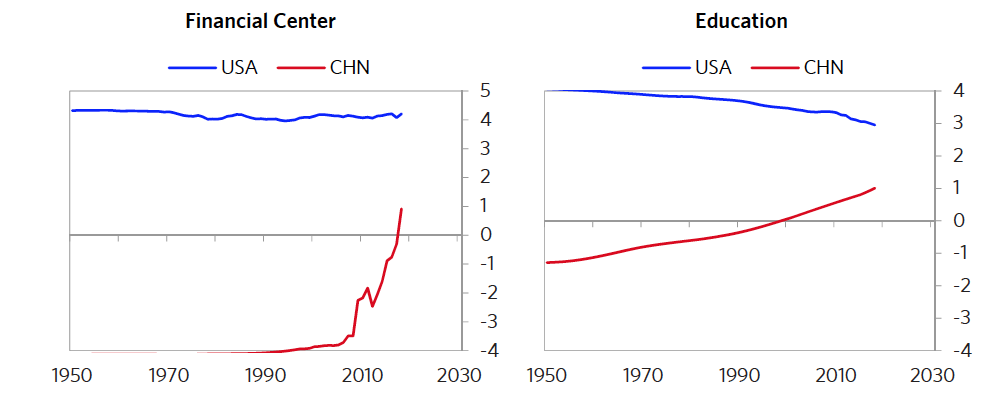

The economics that China is providing these countries is significant and is working in a way that is broadly similar to the way the United States provided economic benefits to key countries after World War II to help secure the desired relationships. America’s influence relative to China’s influence is fading fast. It was not many years ago that there were no significant rivals to the United States so it was quite easy for the United States to simply express its wishes and find that most countries would comply; the only rival powers were the Soviet Union (which wasn’t much of a rival), its allies, and a few of the developing countries that were not economic rivals. Over the last few years Chinese influence over other countries has been expanding while US influence has been receding. That is also true in multilateral organizations—e.g., the United Nations, the IMF, the World Bank, the World Trade Organization, the World Health Organization, the International Court of Justice—most of which were set up by the United States at the beginning of the American world order. As the United States has been pulling back from them, these organizations are weakening and China is playing a greater role in them.

Over the next 5-10 years, in addition to there being the decouplings6 in other areas, we will be seeing which countries align themselves with each of these leading powers. Beyond money and military power, how China and the US interact with other countries (i.e., how they use their soft powers) will influence how these alliances will be made—i.e., style and values will matter. For example, over the last few years I have heard leaders around the world describe both countries’ leaders as “brutal,” which is creating increased fears that they will be punished if they don’t do exactly what these two countries’ leaders want, and they don’t like it to the point of being driven into the other’s arms. It will be important to see what these alliances will look like because throughout history the most powerful country is typically taken down by alliances of less powerful countries that are collectively stronger. Perhaps the most interesting relationship to watch is between China and Russia. Since the new world order began in 1945, among China, Russia, and the United States, two out of the three of them have allied to neutralize or overpower the third. Russia and China each has a lot of what the other needs (e.g., natural resources and military equipment for China from Russia and financing for Russia from China). Also, because Russia is militarily strong it would be a good military ally. We can start to see this happening by watching whether the countries line up on the issues (e.g., whether to allow Huawei in) with the United States or China.

In addition to the international political risks and opportunities there are of course big domestic political risks and opportunities in both countries. That is because there are different factions who are fighting for control of both governments and there will inevitably be changes in leaders that will produce changes in policies that are hard or impossible to anticipate. While nearly impossible to anticipate, these changes are not totally impossible to anticipate because whoever is in charge will be faced with the challenges that now exist and that are unfolding in the Big Cycle ways we have been discussing. Since all leaders (and all other participants in these evolutionary cycles including all of us) step on and get off at different parts of these cycles, they (and we) have a certain set of likely situations to be encountered. Since other people in history have stepped on and off at the same parts of past cycles, by studying what these others encountered and how they handled their encounters at the analogous stages, and by using some logic, we can imperfectly imagine the range of possibilities.

The Capital War

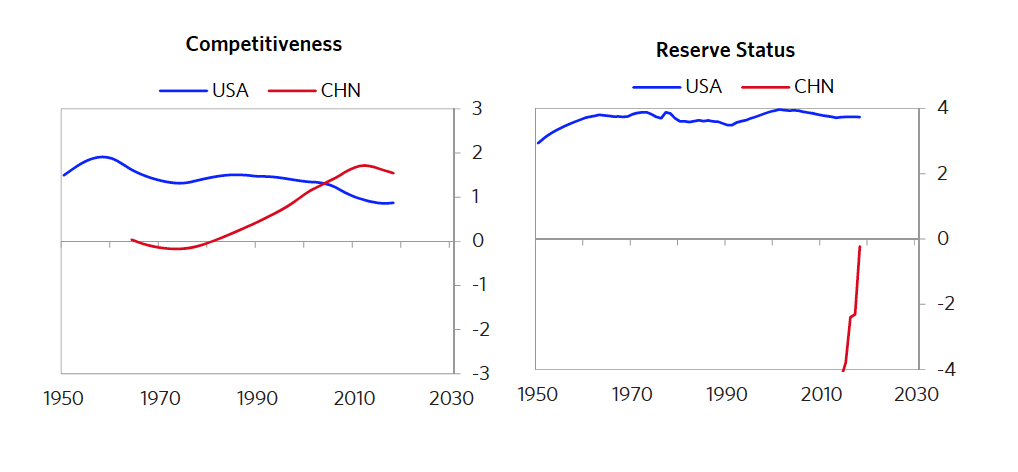

The two main capital war risks are being shut off from capital (which is a greater risk for China than it is for the US) and losing one’s reserve currency status (which is a greater risk for the US than for China).

In Chapter 5 I reviewed classic capital war moves. They are all possibilities in the US-China conflict. The modern term for these moves is “sanctions.” The goal is to cut the enemy off from the capital that the enemy needs because no money = no power. Sanctions come in many forms with the broad categories being financial, economic, diplomatic, and military. Under each of these categories there are many versions and applications. As of 2019, there were approximately 8,000 US sanctions in place targeted at individuals, companies, and governments.7 I’m not going to delve deeper into the various versions and targets because that would be too much of a digression. The main thing to know is that the United States has by far the greatest arsenal of sanctions. Most importantly the United States has the greatest influence over the global financial system and it has the world’s leading reserve currency. That gives it the ability to cut most entities off from receiving money and credit by preventing financial institutions from dealing with them by threatening those financial instructions that deal with the targeted entity with being cut off from the global financial markets. These sanctions are by no means perfect or all-encompassing, but they are generally damned effective.

Because financial market sanctions are so effective they naturally lead those countries that are most likely to be harmed by them to work on approaches either to get around them (e.g., by developing an alternative payment system) or to undermine the United States’ power to impose them. For example, Russia and China, which both are encountering these sanctions and are at much greater risk of encountering more of them, are each now developing and cooperating with the other to develop an alternative payment system. China’s central bank will soon be the first major central bank to propose a digital currency, which will make it more attractive to use. Whatever progress will be made to have China’s currency as a broadly accepted reserve currency at the expense of the dollar will take time and should be viewed as part of the big decoupling phase of the relationship that will take place over the next five years.

The United States’ greatest power comes from being able to print the world’s money (i.e., from having the world’s leading reserve currency) and all the operational powers (e.g., influences on the clearing system) that go along with that. The United States is at risk of losing some of this power while the Chinese are in the position of gaining some of it. That is because the desirability of buying and holding US dollar debt is being reduced because a) the amounts of dollar-denominated debt in foreigners’ portfolios (most importantly in government-controlled portfolios such as central bank reserves and sovereign wealth funds) are disproportionately large based on a number of good long-term measures of what the size of reserve currency holdings should be,8 b) the US government and the US central bank are increasing the amounts of dollar-denominated debt and money at extraordinarily fast paces that are scary and the amounts will be will be hard to find adequate demand for without the Federal Reserve having to monetize a lot of it, c) the financial incentives to hold this debt are unattractive because the US government is paying a negligible nominal yield and a negative real yield on it, and d) holding debt as a medium of exchange or as a storehold of wealth during potential wartime is less desirable than during peacetime. Further, the roughly $1 trillion of debt that China holds (which, by the way, equals only around 4% of the roughly $27 trillion outstanding) is related risk. Also, because other countries realize that actions taken against China could be taken against them, any actions taken against Chinese holdings of dollar assets would likely increase the perceived risks of holding dollar debt assets by other holders of these assets, which would reduce the demand for them. Also, the dollar’s role as a reserve currency largely depends on its being able to be freely exchanged between and working well for most countries, so to the extent that the US puts controls on its flows and/or runs monetary policy in ways that are contrary to the world’s interests in pursuit of its own interests, that makes the dollar less desirable as the world’s leading reserve currency. As you can see these dollar-weakening influences are adding up. At the same time the dollar is in a uniquely strong position because it is so extensively used, which makes it more valuable and less easily replaced.

The United States is testing the limits of how much there can simultaneously be a) enormous amounts of dollar-denominated money and debt created, b) falling and negative real returns, c) the dollar being used as a weapon (e.g., the usage can be limited via capital controls), and d) a fiat monetary system. We won’t know what the limit is and we can’t say it is here until it is reached. At that point it will be too late to fix. From both my studies of past historical extreme cases in which these conditions existed and from our analysis of current and upcoming supplies and demands for US money and debt, one can see that the US government, the Federal Reserve, and the buyers of the debt are testing the limits of how much money and credit can be squeezed out of a reserve currency without breaking it. From speaking to the most knowledgeable people in the world in this domain, including those who are now running the world’s monetary and economic policies and those who did in the past, there isn’t a single person I spoke with who when shown the evidence—i.e., both the historical cases in relation to the current case and the current picture of the supplies and demands for dollar-denominated money and debt—disagrees that we are in unprecedentedly risky territory and testing the limits of what’s possible. That doesn’t mean that anyone is confident that the dollar will decline significantly in value or as a reserve currency in the near future. The picture for the dollar and dollar debt is like (and related to) the picture for interest rates. If a few years ago you had asked whether these extremities would be reached—i.e., whether we would have negative nominal and real long-term interest rates with debts and borrowings so large in a capital market that governments aren’t imposing capital controls on to force such circumstances—all these knowledgeable people would have said “implausible.”That is because that never happened before and because it is tough to figure out why holders and buyers of that debt would accept that deal rather than move their wealth into other things. One would have looked at past extremities when the largest budget deficits and debt monetizations existed in such large amounts and interest rates stayed low (which were war years when government capital controls were required and interest rates were targeted) and looked at the most deflationary and depressing economic times, and one would never have seen these things happen, so “implausible” would have been a smart assessment. Yet that is what has happened.

Now, by watching who bought what for what reasons we can understand why. However, the lesson is the same as one regularly gets in the markets, which is that the implausible happens more often than one would expect. So while most everyone, most importantly the world’s greatest experts, agrees that we are testing the limits, no one, including me, should say with certainty that the dollar will be significantly diminished as a reserve currency anytime soon. However, we can recognize what it will look like when it comes and know that, if it comes, it probably won’t be able to be stopped. There will be a selling of dollar-denominated debt by holders of that debt as they put their assets elsewhere and there will be lot of borrowing of dollar debt by smart debtors who will take advantage of that cheap funding to make higher returns and these moves will require the Fed to choose between a) allowing interest rates to rise unacceptably (because that rise would severely damage markets and the economy) and b) printing money to buy a lot of debt, which will further reduce the real value of the dollar and dollar debt. As described in Chapters 2 and 3, it will look like a classic currency defense. As explained in that chapter, when faced with that choice central banks almost always print money, buy the debt, and devalue the currency, which becomes self-reinforcing because the interest rates being received to hold the currency are not high enough to compensate for the depreciating value of the currency. That continues until the currency and real interest rates reach levels that establish new balance of payments levels, which is a fancy way of saying until there is enough forced selling of goods, services, and financial assets, and enough curtailed buying of them by Americans so they can be paid for with less debt.

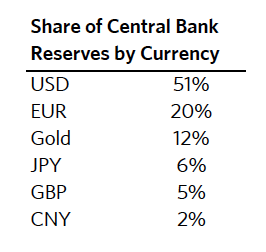

The most often asked question regarding the dollar is, “How could the United States lose its reserve currency status when there are no good alternative currencies to replace it?” So let’s look at that question more closely. The reserve currency assets and their current percentages of total foreign exchange reserves held are as follows:

These six are used in these amounts because of both historical reasons and the fundamentals that affect their relative appeal. As explained and shown in charts earlier in this study, a reserve currency’s usage, like a language’s usage, lags the fundamental reasons for using it by many years because the usage of currency is not easy to change. Right now the four most used reserve currencies—the US dollar, the European euro, the Japanese yen, and the British pound—are of the old leading empires of the post-1945 period though they have limited fundamental appeal. They came from the G5 countries and are about as anachronistic as the G5 is.

As for the fundamental appeal of each of these currencies:

- The dollar was discussed so I won’t repeat the picture.

- The euro is a weakly structured currency made by countries that are tenuously held together by a currency union that is highly fragmented on most issues and economically and militarily weak.

- The yen is a currency that is not widely used internationally by non-Japanese people and suffers from a lot of the same problems that the dollar does, including having too much debt that is increasing quickly and being monetized so that it is paying unattractive interest rates. And Japan is only a moderately powerful country, not a leading power in any important way.

- The British pound is an anachronistically held currency that has relatively weak fundamentals, and the country is relatively weak in most of our measures of a country’s economic/geopolitical power.

- Gold is held because it has worked the best for the longest time and, like the British pound, because it was held from a past time—i.e., before 1971 when gold was at the foundation of the world’s currency system. It has appeal because it doesn’t have the previously described weaknesses of the fiat currencies being overprinted. At the same time the size is limited because the gold market is limited in size.

- The Chinese RMB is the only currency to be chosen as a reserve currency because of its fundamentals—China has the largest share of world trade, its economy is roughly tied for the biggest, it has managed its currency to be relatively stable against other currencies and goods and services prices, and its reserves and its other strengths are large. Also, it doesn’t have the 0% interest rate, negative real interest rate, and the printing and monetization of debt problem though it does have a lot of domestic debt that has to be restructured. Its drawbacks are that it is not widely used, it doesn’t allow the free flowing of capital and a free-floating exchange rate, its capital markets and its financial center have to be better developed, its clearing system is undeveloped, and it has yet to build world investors’ trust.

History has shown that whenever currencies are not desired they are sold off and devalued with the capital finding other investments (e.g., gold, silver, stocks, property, etc.) to go into, so there is no need to have an attractive alternative foreign currency market to go into for the devaluation of a currency to occur. In other words the US could see its reserve currency status reduced without there being an alternative reserve currency to go into.

Without the US disrupting China’s currency and capital markets they will likely develop quickly and increasingly compete with the US currency and credit markets. You won’t see this all at once, but you will see it evolve that way at a shockingly fast pace over the next 5-10 years. As shown in the Dutch, British, and US cases that development is consistent with the natural arc of things. Also, the fundamentals are in place for that to happen if the Chinese continue to run sound policies and develop their markets well. There is a lot of potential for Chinese capital markets, the RMB, and RMB-denominated debt to grow in importance because it is so underinvested in relative to its fundamentals. For example:

- China and the US are the largest trading countries, both accounting for about 13% of global trade (including exports and imports), yet the RMB accounts for only about 2% of world trade financing while the dollar accounts for over 50%. It would be pretty easy to increase the share of trade financing in RMB.

- While China accounts for around 19% of world GDP9 (and is growing at a faster rate than the US) and has around 15% of global equity market capitalization, it has only about 5% weight currently in MSCI equity indices and its assets represent only about 2% of foreign assets in portfolios. In contrast while the United States on the whole accounts for around 20% of world GDP and is growing slower, it now accounts for over 50% weight in MSCI equity indices and has around 48% of non-American money in it. My point is that Chinese markets are underinvested in because the investment has lagged the development, especially for foreign investors.

As previously explained and shown in the development of the Dutch, British, and American empires, the development of the world’s leading capital markets and the world’s capital market centers of Amsterdam, London, and New York was an essential step in each empire’s development to become the leading empire and has traditionally lagged the country’s fundamentals the way the Chinese capital markets and Shanghai as a financial center (and to a lesser extent Hong Kong and Shenzhen) have lagged China’s developments.

The development of Chinese currency and capital markets would be detrimental for the United States and beneficial for China. So once again it seems likely that American policy makers will be forced to choose between a) trying to disrupt this evolutionary path by becoming more aggressive with their wars (in this case via a more aggressive capital war) and b) accepting that evolution will likely lead to China becoming relatively stronger, more self-sufficient, and less vulnerable to being squeezed by the US at the expense of US leadership in this area, especially over the next 5-10 years. We are seeing some early signs of US moves to curtail Americans’ investments in Chinese markets and to possibly delist Chinese companies from American stock exchanges. These are double-edged swords because while being marginally harmful to Chinese markets and listed companies they also weaken American investors’ and American stock exchanges’ abilities to be competitive, which will support the development of those in China and elsewhere. For example, the Ant Group’s choice to list on the Hong Kong and Shanghai exchanges gives investors the choice of investing on those Chinese exchanges or missing out on those investments, which are listed there and not on other exchanges.

The Military War

I am not a military expert but I get to speak with military experts and I do research on the subject so I will pass along what has been given to me. Take it or leave it at your own peril.

It is impossible to visualize what the next major war will be like, though it probably will be much worse than most people imagine. That is because a lot of weaponry has been developed in secret and because the creativity and capabilities to inflict pain have grown enormously in all forms of warfare since the last time most powerful weapons were used and seen in action. There are now more types of warfare than one can imagine and, within each, more weapons systems than anyone knows. While of course nuclear warfare is a scary prospect I have heard equally scary prospects of biological, cyber, chemical, space, and other types of warfare. Many of these have been untested so there is a lot of uncertainty about how they will work.

Based on what we do know the headline is that a) the United States and China’s geopolitical war in the East and South China Seas is escalating militarily because both sides are testing each other’s limits, b) China is now militarily stronger than the United States in the East and South China Seas so the US would probably lose a war in that region, while c) the United States is stronger around the world and overall and would probably “win” a bigger war, though d) a bigger war is too complicated to imagine well because of the large number of unknowns, including how some other countries would behave in it and what technologies secretly exist. The only thing that most informed people agree on is that such a war would be unimaginably horrible.

Also notable, a) China’s rate of improvement in its military power, like its other rates of improvement, has been extremely fast, especially over the last 10 years, and b) the rate of progress in the future is expected to be even faster, especially if its economic and technological improvements continue to outpace those of the United States. Some people imagine that China could achieve broad military superiority in 5-10 years.

As for potential locations of military conflict, Taiwan, the East and South China Seas, and North Korea are the biggest hot spots, and India and Vietnam are the next biggest (for reasons I won’t digress into).

As far as a big hot war between the United States and China is concerned, it would include all the previously mentioned types of wars plus more pursued at their maximums because, in a fight for survival, each would throw all they have at the other, the way other countries in history have, so it would be World War III, and World War III would likely be much more deadly than World War II, which was much more deadly than World War I because of the technological advances that have been made in the ways we can hurt each other.

In thinking about the timing of a war, I keep in mind the principle that when countries have big internal disorder, it is an opportune moment for opposing countries to aggressively exploit their vulnerabilities. For example, the Japanese made their moves to take control of European colonies in Southeast Asia in the 1930s when the European countries were challenged by their depressions and their conflicts. History has also taught us that when there are leadership transitions and/or weak leadership, at the same time that there is big internal conflict, the risk of the enemy making an offensive move should be considered elevated. For example, those conditions could exist in the upcoming US presidential election. However, because time is on China’s side (because of the trends of improvements and weakenings shown in prior charts), if there is to be a war, it is in the interest of the Chinese to have it later (e.g., 5-10 years from now when it will likely be more self-sufficient and stronger) and in the interest of the US to have it sooner.

I’m now going to add two other types of war—1) the culture war, which will drive how each side will approach these circumstances, including what they would rather die for than give up, and 2) the war with ourselves, which will determine how effective we are, which will lead us to be strong or weak in the critical ways that we previously explored.

The Culture War

How people are with each other is of paramount importance in determining how they will handle the circumstances that they jointly face, and the cultures that they have will be the biggest determinants of how they are with each other. What Americans and the Chinese value most and how they think people should be with each other determine how they will deal with each other in addressing the conflicts that we just explored. Because Americans and the Chinese have different values and cultural norms that they will fight and die for, if we are going to get through our differences peacefully it is important that both sides understand what these are and how to deal with them well.

As described earlier, Chinese culture compels its leaders and society to make most decisions from the top down, demanding high standards of civility, putting the collective interest ahead of individual interests, requiring each person to know their role and how to play it well, and having filial respect for those superior in the hierarchy. They also seek “rule by the proletariat,” which in common parlance means that the benefits of the opportunities and fruits of productivity created are broadly distributed. In contrast American culture compels its leaders to run the country from the bottom up, demanding high levels of personal freedom, favoring individualism over collectivism, admiring revolutionary thinking and behavior, and not respecting people for their positions as much as for the quality of their thinking. These core cultural values drove the type of economic and political systems they chose.

To be clear, most of these differences aren’t obvious in day-to-day life; they generally aren’t very important relative to the shared beliefs that Americans and the Chinese have, which are numerous, and they aren’t held by all Chinese or all Americans, which is why many Americans are comfortable living in China and vice versa. Also, they are not pervasive. For example, the Chinese in other domains such as Singapore, Taiwan, and Hong Kong have governance systems that are more like Western democratic systems. Still these cultural differences subtly affect most everything, and in times of great conflict, they are the defining differences that determine whether the parties fight or peacefully resolve their disputes. The main challenge the Chinese and Americans have with each other arises from some of them failing to understand and empathize with the other’s values and ways of doing things, and not allowing each other to do what they think is best. While the openings up of both countries have increased their interactions and their increasingly shared practices (e.g., their similar economic freedoms that produce similar desires, products, and outcomes) have made both environments and their people much more similar than they ever were, the differences in approaches are still notable. They are reflected regularly in how the government and the people within each country interact with each other and how Americans and the Chinese interact especially at the leader-to-policy-maker level. Some of these cultural difference are minor and some of them are so major that many people would fight to the death over them—e.g., most Americans believe “give me liberty or give me death” while individual liberty isn’t nearly as important to the Chinese as collective stability is.

These differences become reflected in differences in everyday life. For example, the Chinese government, being more paternal, regulates what types of video games are played by children and how many hours a day they can play them, whereas in the United States they aren’t government-regulated because it is considered an individual parent’s decision to make. One could argue the merits of either approach. The Chinese hierarchical culture makes it natural for the Chinese to simply accept the government’s direction while the American non-hierarchical culture makes it acceptable for Americans to fight with their government over whether or not to do it that way. Similarly different cultural inclinations affect how Americans and the Chinese react to being told that they have to wear masks in response to COVID-19, which leads to second-order consequences because the Chinese follow the instructions and Americans don’t—numbers of cases, deaths, economic impacts, etc. These culturally determined differences in how things are handled affect how the Chinese and Americans react differently to many things—e.g., information privacy, free speech, free media, etc.—which add up to lots of ways that the countries operate differently.

While there are pros and cons to these different cultural approaches to handling things and I’m not going to explore them here, I do want to get across that the cultural differences that make Americans Americans and the Chinese Chinese are deeply embedded in them so one can’t expect the Chinese not to be Chinese and Americans not to be Americans. In other words, one can’t expect the Chinese to give up what they deeply believe are the right and wrong ways for people to be with each other. Given China’s impressive track record and how deeply imbued the culture behind it is, there is no more chance of the Chinese giving up their values and their system than there is of Americans giving up theirs. Trying to force the Chinese and their systems to be more American would to them mean subjugation of their most fundamental beliefs, which they would fight to the death to protect. To have peaceful coexistence Americans must understand that the Chinese believe that their values and their approaches to living out these values are best as much as Americans believe their American values and their ways of living them out are best.

For example, one should accept the fact that when choosing leaders most Chinese believe that having capable, wise leaders make the choices is preferable to having the general population make the choice on a “one person one vote” basis because they believe that the general population is less informed and less capable. Most believe that the general population will choose the leaders on whims and based on what those seeking to be elected will give them in order to buy their support rather than what’s best for them—e.g., the general voting population will choose those who will give them more money without caring where the money comes from. Also, they believe—like Plato believed and as happened in a number of countries that turned from democracies to autocracies through the millennia (most recently in the 1930-45 period)—that democracies are prone to slip into dysfunctional anarchies during very bad times while people fight over what should be done rather than support the strong, capable leader who will tell them what they should do. They also believe that their system of choosing leaders lends itself to better multigenerational strategic decision making because any one leader’s term is only a small percentage of the time that is required to progress along that developmental arc.10 They believe that what is best for the collective is most important and best for the country and is best determined by those at the top. Their system of governance is more like the governance that is typical in big companies, especially multigenerational companies, so they wonder why it is hard for Americans and other Westerners to understand the rationale for the Chinese system following this approach and to see the challenges of the democratic decision-making process as they see them. To be clear I’m not seeking to explore the relative merits of these decision-making systems; I am simply trying make clear that there are arguments on both sides and to help Americans and the Chinese see things through each other’s eyes, most importantly, to understand that the choice is between a) accepting, tolerating, and even respecting each other’s right to do what each thinks is best and b) having the Chinese and Americans fight to the death over what they believe is uncompromisable.

The American and Chinese economic and political systems are different because of the differences in their histories and the differences in their cultures that resulted from these histories. As far as economics is concerned—i.e., 1) the classic left (favoring government ownership of the means of production, the poor, the redistribution of wealth, etc.), which the Chinese call communism, and 2) the classic right (favoring private ownership of the means of production, whoever succeeds in the system, and much more limited redistributions of wealth)—exists and has had swings from one to the other in all societies especially in China, so it would not be correct to say that the Chinese are culturally left or right. Similar swings in American preferences have existed throughout its much more limited history. I suspect that if the United States had a longer history we would have seen wider swings as we have seen in Europe through its longer history, so we should consider even wider swings possible. For these reasons these “left” versus “right” inclinations appear to be more Big Cycle swings around the evolutionary trends than core values that are evolving. In fact we are seeing these swings now taking place in both countries so it’s not a big stretch to say that policies of the “right” such as capitalism are close to being more favored in China than in the United States and vice versa. In any case, the deep cultural preferences and the clear distinctions are not there. In contrast the cultural inclinations of the Chinese to be top-down/hierarchical versus bottom-up/non-hierarchal are deeply embedded in them and in their political systems and the cultural inclinations of Americans to be bottom-up/non-hierarchal are also deeply embedded in them. As for which approach will work best and will win out in the end, I will leave that for others to debate, hopefully without bias, though I will note that most knowledgeable observers of history have concluded that neither of these systems is always good or bad—that what works best varies according to a) the circumstances and b) how people using these systems are with each other. No system will sustainably work well, in fact all will break down, if a) the individuals in it don’t respect it more than what they individually want and b) the system is not flexible enough to bend with the times without breaking.

So now, as we imagine how Americans and the Chinese will handle their shared challenge to evolve in the best possible way on this shared planet, I try to imagine where their strong cultural inclinations, most importantly where the irreconcilable differences that they would rather die for than give up, will lead them.

For example, most Americans and most Westerners would fight to the death for a) the ability to have and express one’s opinions, including one’s political opinions, and b) the lack of the right and ability of the organization they are part of to stand in the way of that right. In contrast the Chinese value more a) the respect for authority, which is reflected and demonstrated by the relative parties’ powers, and b) the responsibility to hold the collective organization responsible for the actions of individuals in the collective. A recent example of such a culture clash occurred when in October 2019 the general manager of the Houston Rockets (Daryl Morey) tweeted an image expressing support for Hong Kong’s pro-democracy protest movement. He quickly pulled down his tweet and explained that his views weren’t representative of his team’s views or the NBA’s views. Morey was then attacked by the American side (i.e., the press, politicians, and people) for not standing up for free speech and by the Chinese side, and the Chinese side held the whole league responsible and punished it by dropping all NBA games from China’s state television, pulling NBA merchandise sales from online stores, and demanding that the league fire Morey for expressing his critical political views. This culture clash arose because of how important free speech is to Americans and how Americans believe that the organization that the individual is a part of should not be punished for the actions of the individual. The Chinese, on the other hand, believe that the harmful attack needed to be punished and that the group that the individual is a part of should be held accountable for the actions of the individuals in it. One might imagine much bigger cases in which much bigger conflicts would arise due to such differences in deep-seated beliefs about how people should be with each other. For example, when in a superior position, the Chinese tend to want that to be clear, to have the party in a subordinate position know that it is in a subordinate position and to obey and that, if it doesn’t do these things, it will be punished. That is the cultural inclination/style of Chinese leadership. They can also be wonderful friends who will provide support when needed. For example, when the governor of Connecticut was desperate to get personal protective equipment in the first big wave of COVID-19 illnesses and deaths and couldn’t get it from the US government and other American sources, I turned to my Chinese friends for help and they provided what was needed, which was a lot. As China goes global a number of countries’ leaders (and their populations) have been both grateful and put off by China’s acts of generosity and strict punishments. Some of these cultural differences can be negotiated to the parties’ mutual satisfaction but some of the most important ones will be very difficult to negotiate away.