Good Articles to Share

"If you build it (revenues), they (profits) will come": Amazon's Field of Dreams! - Aswath Damodaran

Tan KW

Publish date: Thu, 30 Oct 2014, 10:16 AM

Wednesday, October 29, 2014

I have a long standing fascination with Amazon from its inception as a dot-com poster child in the late 1990s to its current standing as online retailer to the world. I have always liked the company's willingness to challenge established rules on how business should be done and admired Jeff Bezos for being to willing to leap into places where others only tip toe. As an investor, though, I have found the company to be cheap at times in the last 15 years and expensive at others, and the most recent earnings report led me to revisit it, partly to examine whether the market's negative reaction to the most recent earnings report was appropriate and partly because I may learn something.

A short history of Amazon

For those are twenty five or younger, it is hard to imagine a world without online retailing, in general, and Amazon, in specific, but it was just over 20 years ago (in July 1994), that Amazon was founded by Jeff Bezos in his garage, continuing the long tradition of garage-founded companies in the United States. The company caught the dot-com wave of the late 1990s and was listed on the NASDAQ in 1997. Initially focused on book retailing, the company remained small in operating numbers, relative to other retail giants, and generated only $1.6 billion in revenues in 1999, while reporting an operating loss of almost $600 million. Its market capitalization, though, rocketed up (with the rest of the dot-com sector), hitting $ 35 billion in early 2000. In fact, it was one of the companies that I used as a prop for a book I had on valuing young, technology companies. At the risk of gravely embarrassing myself, this was my valuation of Amazon in January 2000, close to its peak:

|

| My valuation of Amazon in January 2000 (The Dark Side of Valuation) |

It is never flattering to the ego to compare actual to forecasted numbers, especially for young growth companies but it is a process that has never bothered me, because it comes with the territory. I compare my forecasted revenues & operating income for Amazon (from my January 2000 valuation) to the actual revenues & operating income for the company (from 2000 to 2013) in the table below.

|

| Comparison of my forecasts in 2000 to actual numbers |

I will cheerfully confess that I did not have the foresight to predict the behemoth that Amazon would become in retailing and the tentacles that it put into other businesses (including media and cloud data) but my forecasted revenues were higher than the actual numbers every year through 2010. Since 2010, though, the company has blown the lid of my revenue forecasts but that outperformance has come at a price. I may have been pessimistic in my assessments of Amazon's capacity to scale up its revenues, but I was also overly optimistic in assuming that it would find a pathway to strong profitability. After mounting a steady improvement in margins in the first half of the last decade, the company seems to have relapsed in the last few years.

A Field of Dreams company

A couple of years ago, James Stewart wrote an article in the New York Times, using Amazon to draw a contrast between short-term markets and long-term managers. The discussion about whether markets are short term and if so, why, is one well worth having, but I took issue with Mr. Stewart on his use of Amazon as an example of short term markets. In fact, I would argue that markets have been extraordinarily forgiving of Amazon's long loss-making history and have given Mr. Bezos breaks that very few companies have received through time. If anything, they have been too "long term" in their thinking, not too "short term".

In keeping with my obsession with popular culture, the movie that comes to mind whenever Amazon reports yet another earnings report, with strong revenue growth and increasing losses, is the Field of Dreams, with this scene, in particular, playing out.

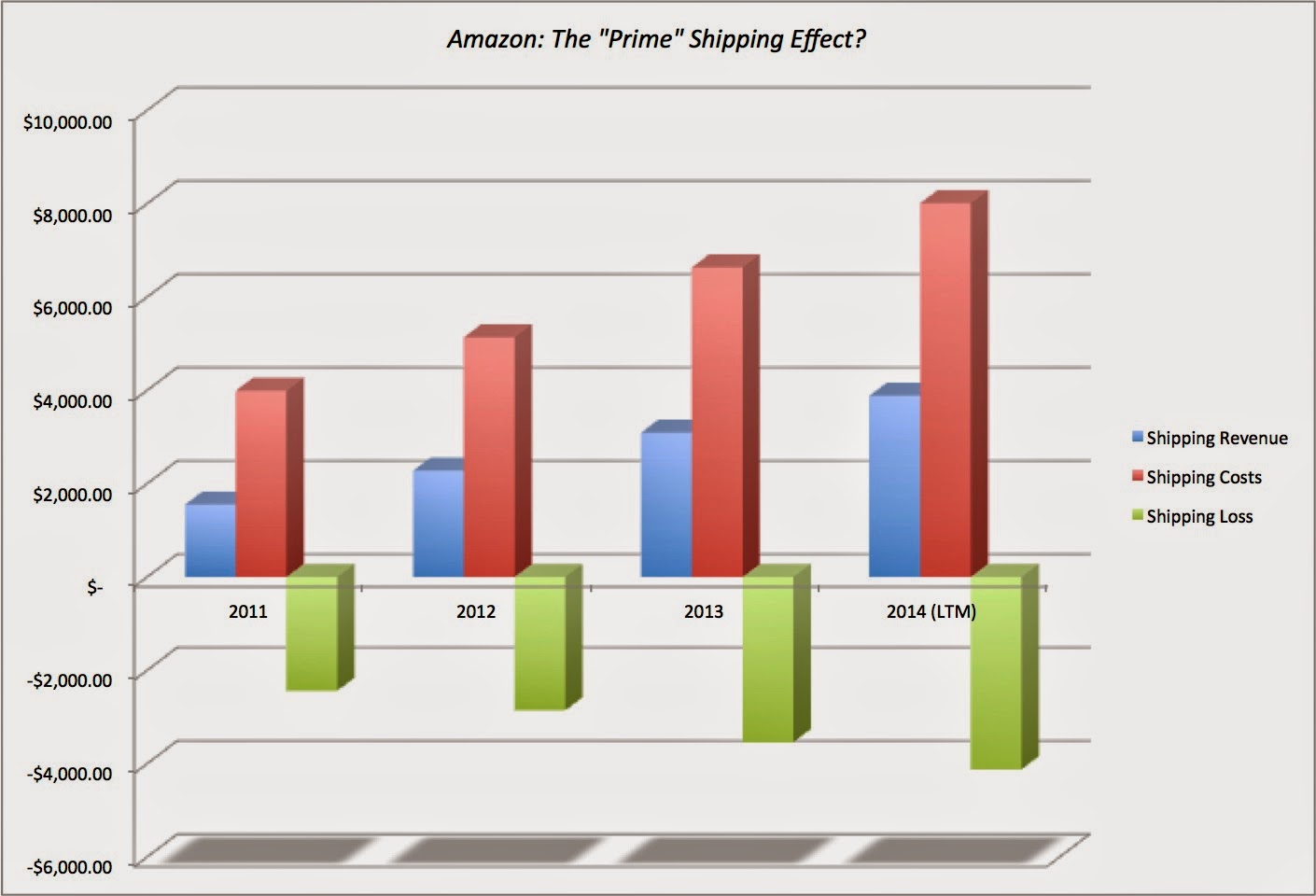

As I see it, Jeff Bezos has built the ultimate field of dreams company (and I don't mean that in a dismissive way), where he has sold investors on the notion that if he builds revenues up, the profits will come. The losses at Amazon are thus a deliberate consequence of the way the company approaches business, selling products and services below cost and with lots of hype, with the intent of inserting themselves in peoples' lives so completely that they will be unable to abandon the company in the future. To provide a simple illustration of this process, consider one of Amazon's most successful services, Amazon Prime, to which I am a subscriber. At $99/year, it is a bargain, since the shipping costs I save vastly exceed the cost of the service. While that may reflect my family's profligate spending habits, there is some evidence in Amazon's own financials that the cost of providing this service significantly exceeds the revenues that they collect from it. In the figure below, I compare shipping revenues and costs reported by Amazon each year for the last few years.

|

| From Amazon financial filings |

Not only has Amazon lost billions on shipping each year, but its losses have become larger over time. In fact, you can take many of Amazon's recent innovations (including the Kindle) and put them to the profitability test and will find them falling short. I am sure that Amazon's cheerleaders will argue that both the Prime and Kindle create synergistic benefits to Amazon, but in that argument would have resonance, if the company made money in the aggregate.

Valuing Amazon

At this stage, the value of Amazon rests on how much you trust the vision that Jeff Bezos has for the company and whether you believe in his capacity to fulfill that vision. In fact, the value of Amazon will be largely determined by your assumptions about revenue growth and operating margins. To provide perspective, let’s start by looking at where Amazon falls in the competitive spectrum by looking at the retail sector as a whole. In the table below, I list the ten largest retailers in the US and globally, in terms of revenues:

|

| Largest Retail Companies: Trailing 12 month data (on 10/29/14) |

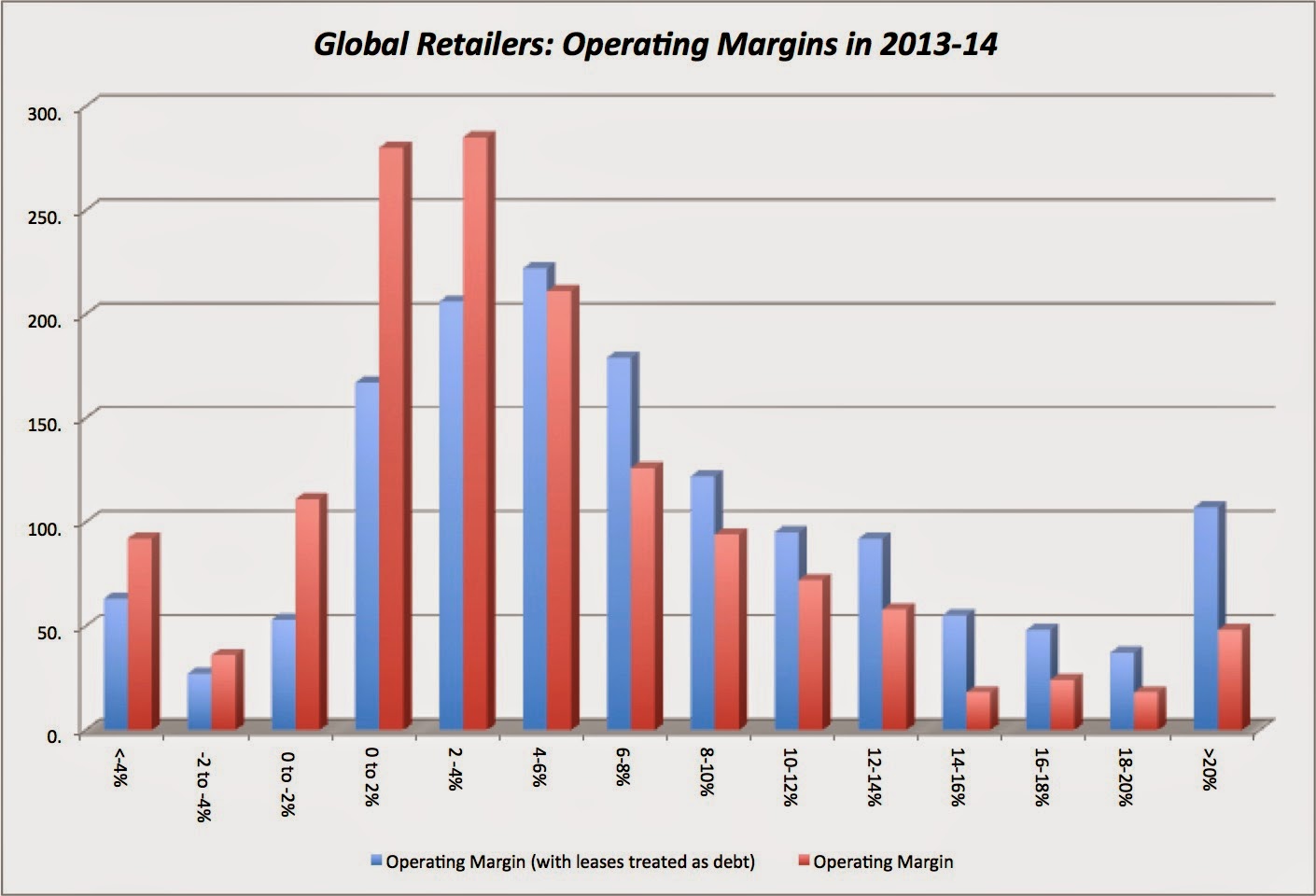

Note that while Amazon makes the top ten lists in terms of revenues both in the US and globally, it lags in terms of profitability with paper-thin operating margins. To get a measure of profitability in the retail sector, I estimated operating margins (converting leases to debt) for all retail firms and report the distribution in the graph below (for both the conventional pre-tax operating margin, which is operating income as a percent of sales, and a lease-adjusted operating income, where leases are converted to debt).

Since many of the firms in this sample are small, with revenues of a billion or less, I looked at the pre-tax operating margin for firms in different revenue classes and the results are not surprising, with margins decreasing as revenues increase.

|

| Source: S&P Capital IQ, Trailing 12 month data (October 2014) |

The median pre-tax operating margin for a US retailer with at least $1 billion in sales is 7.67% and the 75th percentile is 11.99%, but the median operating margin for US retailers with more than $10 billion in sales drops to 5.14% and the 75th percentile is 10.17% (and the 25th percentile is only 2.85%). It is true that Amazon also draws revenues from its media and cloud computing businesses and that the margins are higher at least in the media business. Using a (revenue) weighted average of the operating margins across the businesses (with the weights based on Amazon's mix of media and retail) yields values of 4.35%, 7.38% and 12.84% for the 25th percentile, median and the 75th percentile.

If you assume that Amazon will continue its steep revenue growth into the future (and is able to grow revenues to about $250 billion by 2024) and that its operating margin will converge on the weighted median operating margin for the retail and media sectors (7.38%), the value of equity that you obtain is about $81 billion (or $175/share). You can download the spreadsheet that contains the Amazon valuation. If you are bullish on Amazon, at its current stock price, you have to be either be expecting even higher revenues (than $250 billion) in 2024 than or much higher steady state margins (than 7.38%), with the best-case scenario being one where Amazon continues growing revenues significantly, driving its competitors into bankruptcy, and then uses its market power to charge higher prices and generate high profit margins. Thus, assuming a 12.84% operating margin (the weighted average of the 75th percentiles), in conjunction with the revenues forecast in the base case, would yield a value per share of $345/share, higher than the current stock price of $295.

Rather than play scenario games, I chose to vary revenue growth and operating margins to see the combinations that deliver values (shaded in yellow) that exceed the current stock price ($295) in the table below:

I draw three lessons from this table. The first is that there are pathways that Amazon can follow that deliver values greater than $292 but they are narrow and require a combination of high revenue growth and high operating margins, and some of these combinations may expose the company to anti-trust action down the road. The second is that the variable that makes the bigger difference is the operating margin, not revenue growth. In fact, if the margin stays at 2.5%, higher revenue growth causes value to decline as the cost of increasing revenues (acquisitions and reinvestment) exceed the benefits. The breakeven operating margin at which growth even starts to create value is about 4%. and if the operating margin stays at 7.5% or lower, you cannot get above the current stock price, even with Walmart-like revenues. The third is that the potential for explosive returns is low, given the current stock price. While there are combinations of revenue/margin that deliver values well above $295, they seem improbable, requiring Amazon to have revenues like Walmart and margins like Lululemon.

Bottom line

In a world of cookie-cutter CEOs, uninspired and uninspiring, eager to please analysts (rather than investors) and playing the me-too game (You can buy back stock, me too! You can do acquisitions, me-too!), Jeff Bezos offers a refreshing contrast. He has a vision for Amazon, has communicated it to markets with passion and has acted consistently with that vision, and has been rewarded by markets with a high market value for his company, even in the absence of profitability. However, the peril with charismatic CEOs is that the strength and single-mindedness that make them so successful can become weaknesses, if they start believing the hype. As a consumer, I am delighted that I get Amazon Prime for $99 a year, that the Kindle costs a lot less than an iPad and that I can (though I don’t plan to) pick up the Amazon Fire for nothing, but as an investor, this is not a winning game. Mr. Bezos has delivered on half of his field of dreams vision by building up the revenues for Amazon, but the other (and more difficult) half of the vision requires that the “profits” arrive. Much as I would like to believe in miracles, it is take far more work to make Amazon profitable than it would to make Shoeless Joe Jackson show up in a cornfield in Iowa!

Attachments

http://aswathdamodaran.blogspot.com/2014/10/if-you-build-it-revenues-they-profits.html

More articles on Good Articles to Share

Some investors demand change at LVMH after probe into Dior contractors

Created by Tan KW | Jul 23, 2024

US existing home sales slump in June; median price hits record high

Created by Tan KW | Jul 23, 2024

US spot ether ETFs make market debut in another win for crypto industry

Created by Tan KW | Jul 23, 2024

French leftists announce legislative steps to scrap Macron's pension reform

Created by Tan KW | Jul 23, 2024

Kenya police fire tear gas to stop scuffles between pro and anti-government groups

Created by Tan KW | Jul 23, 2024

Some investors demand change at LVMH after probe into Dior contractors

Created by Tan KW | Jul 23, 2024

Coca-Cola lifts annual forecasts as price hikes fail to dampen soda demand

Created by Tan KW | Jul 23, 2024

ipomember

awesome article. thanks kw

2014-10-30 10:30