Corporate structure determines the fate of a nation By NG ZHU HANN

savemalaysia

Publish date: Sat, 11 Sep 2021, 10:33 AM

THERE was once a boy in South Korea who lived in poverty, growing up with five siblings raised by his grandmother, in a one bedroom apartment within the poorest neighbourhood of Seoul.

His father was a pen factory worker while his mother was a hotel housekeeper.

Despite the adversity in life, he was extremely driven and often motivated himself by writing Korean quotes in his own blood.

He was the first of his family to go to college and gain admittance in 1986 at the prestigious Seoul National University. There, he learnt about the Internet and embarked on his entrepreneurship journey through technology.

He is Kim Beom-soo (also known as Brian Kim), the founder of Internet giant, Kakao. Kim overtook Samsung’s heir Lee Jae-yong as the richest South Korean on 23rd of June with a net worth of US$16.2bil following his company’s share price ascend by more than 110% in 2021.

Apart from the heartwarming rags to riches element to this story, what is especially significant is the fact that South Korea’s economy have always been dominated by “Chaebols” for most of the past century.

The word Chaebol is a combination of the South Korean words chae (wealth) and bol (clan or clique). It essentially means family-run conglomerates with businesses across diverse industries.

Chaebols rose to prominence post 1950s Korean War as it played a key role in lifting the war torn nation out of poverty and rebuilding the economy for its citizens. It relied heavily on government support as well as favourable policies to build up its market position. It was a win-win arrangement for the country as the government needed to create employment, feed the people and grow the domestic economy. Chaebols became the prime vehicle that steered the country forward.

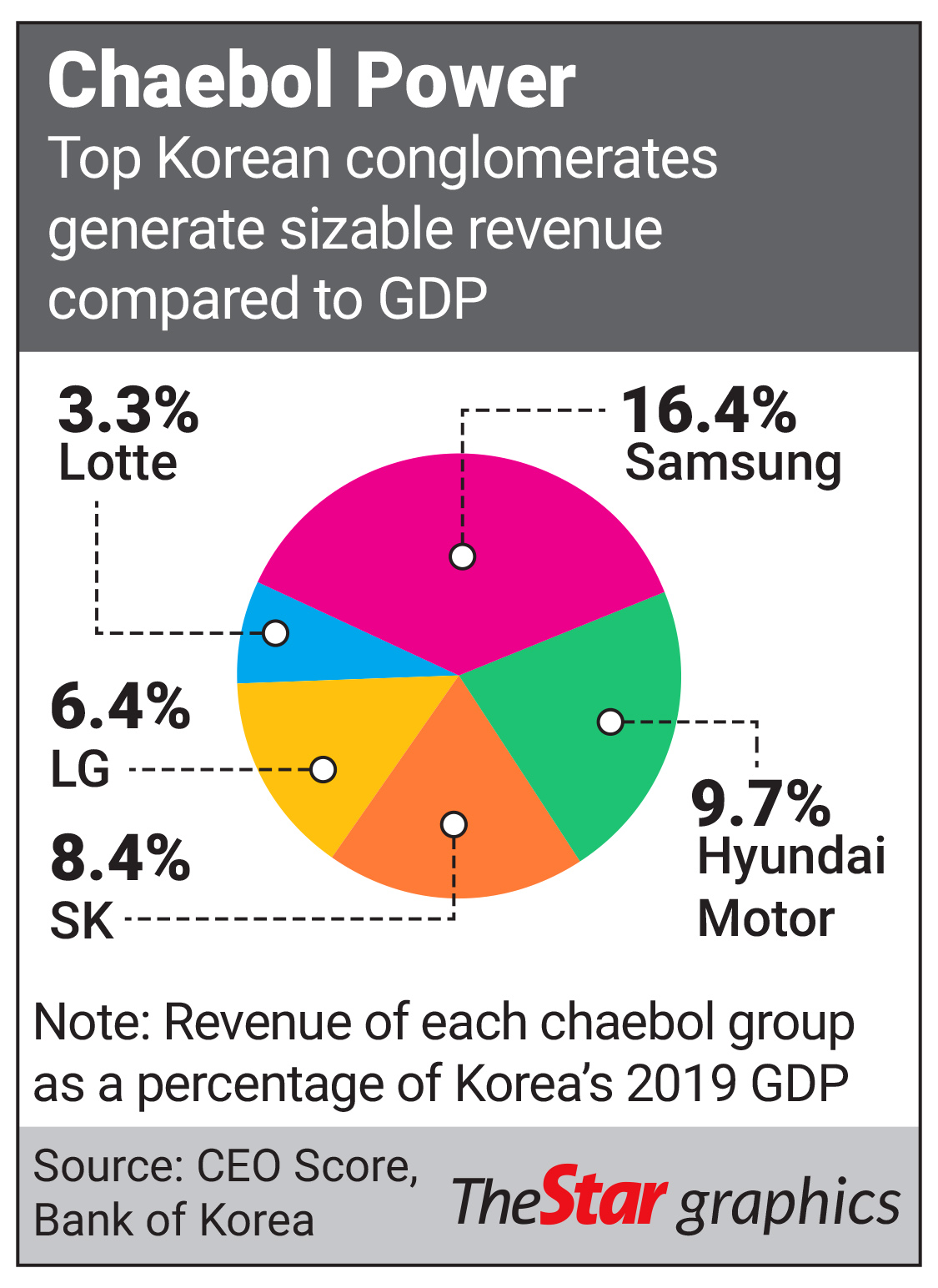

Today, they have grown so big that it has overbearing influence not only within South Korea but globally with household names like Samsung, Hyundai, LG, SK and Lotte. The pie chart above shows the percentage of revenue as compared to the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) for the five biggest South Korean conglomerates as at 2019.

What is particularly fascinating is the concentration of wealth and influence on business entities like the Chaebols that can be found in other Asian countries as well.

In Japan, there are the large general trading companies with hundreds of years of history known as the “sogo shosha”. These companies has its roots in 1800s when Japan opened up to foreign trade during the Meiji-era.

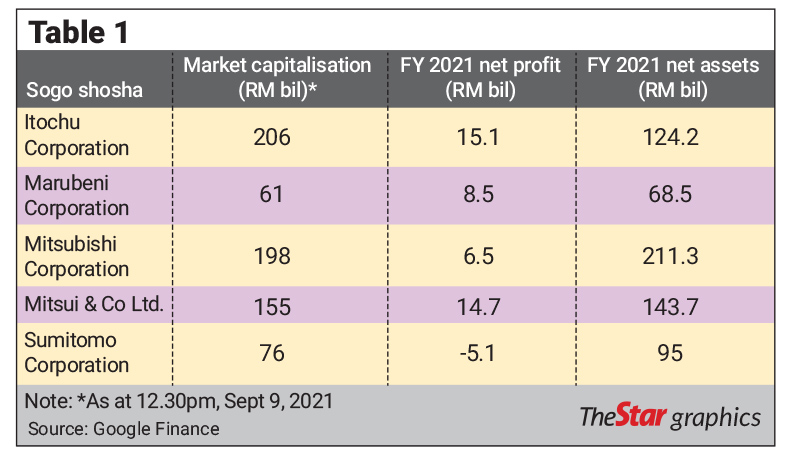

Many have grown from textile manufacturers and steel makers to diversified industries across finance, real estate, banking, insurance, automotive sectors among others. In Japan today, there are seven notable “sogo shosha” remaining namely Toyota Tsusho, Sojitz, Itochu, Marubeni, Mitsubishi, Mitsui, and Sumitomo. Legendary investor Warren Buffett spent US$7bil in 2020 taking a 5% stake in five of them as per Table 1.

Buffett rarely invest overseas as he is a perpetual believer in the prospect of the United States with his famous quote “never bet against America”. For Berkshire Hathaway to see value in these “sogo shosha” indicates they are well-run quality companies.

Closer to home, the government linked companies (GLC) or government linked investment companies (GLIC) structure is more prevalent. This is similar to Singapore.

The reason Malaysia and Singapore adopted this structure is due to the national agenda pursued by both countries over the past decades. Both were relatively young nations in 1990s since its independence from the British. In order to spur economic growth and create vast employment in the private sector for a burgeoning population, GLC and GLIC took centre stage.

Based on a 2018 research by Jayant Menont of Asian Development Bank, GLCs account for about half of the FBM KLCI and constitute seven out of the top-10 listed firms in 2018.

Globally, Malaysia ranks fifth-highest in terms of GLC influence on the economy. These findings were corroborated by professor Terence Gomez’s research which showed how seven GLIC control 68,000 companies be it directly and indirectly.

In addition, they have majority ownership of 35 public-listed companies and control 42% of the market capitalisation of the entire Bursa Malaysia then. The seven GLICs highlighted were Minister of Finance Inc, Permodalan Nasional Bhd, Khazanah Nasional Bhd, Kumpulan Wang Persaraan, Employees Provident Fund, Lembaga Tabung Haji and Lembaga Tabung Angkatan Tentera.

While I am not keen to dwell into the performance of the GLCs and GLICs in this column, I believe there are merits for their existence. This parallel is drawn mainly to show how our country’s economy is driven by certain corporate structure.

In May 2004, the GLC Transformation Programme was launched by the government to enhance financial performance, institutionalise good governance and deliver impactful contributions to national socioeconomic development. On Aug 12, former Prime Minister Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin launched a three-year Perkukuh Pelaburan Rakyat programme to reform and future-proof GLIC to ensure they remain relevant over the longer term.

For whatever their worth, GLC and GLIC have a very important role to play in the Malaysian economy, more so now than ever due to the economic slump as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Official statistics show there are 900,000 small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in the country hiring 50% of the workforce (an estimate of 7.3 million people). SMEs contribution to the economy stands at 38% in 2020 amounting to RM512.8bil. This underscores the importance of SMEs in our economy structure as a whole. Despite so, SMEs have suffered the biggest brunt in terms of economic impact due to the pandemic.

A good place to start for the GLC and GLIC is to assist in supporting and rebuilding the SMEs while nurturing next generation entrepreneurial talents that will inject life into the private sector beyond the traditional ecosystem. This means churning out talents who can become business builders, whose enterprise in turn help grow the economic pool of Malaysia.

Kim spent five years working in Samsung’s subsidiary information technology services group before he scraped together US$184,000 from friends and family to launch an online gaming company.

Fellow self-made billionaire Lee Hae Jin who founded Naver, the equivalent of Google of South Korea which also owns popular messaging app Line, had also worked in Samsung SDS where he met Kim. Both self-made entrepreneurs started out in a Chaebol only to venture out and successfully built a nation changing enterprise.

Regardless of whether it is the Chaebol, “Sogo shosha” or GLC, whichever company structure adopted to drive the economy of a nation, it is good to have a healthy balance and serve the greater good of the people. Apart from the usual metrics such as employment opportunities, career development, wage growth, these corporate vehicles must be able to keep up with the times by remaining ahead of the curve and competitive with regional peers.

There is no point being a “Jaguh Kampung” but falling behind other countries. In the short term, it may address pain points but in the long run, it will cause structural damage which would be hard to overcome.

Hann, is the author of Once Upon A Time In Bursa. He is a lawyer and former chief strategist of a Fortune 500 Corp. The views expressed here are the writer’s own.

https://www.thestar.com.my/business/business-news/2021/09/11/corporate-structure-determines-the-fate-of-a-nation

More articles on save malaysia!

Created by savemalaysia | Jun 02, 2024

Created by savemalaysia | Jun 02, 2024

Created by savemalaysia | Jun 01, 2024

Created by savemalaysia | Jun 01, 2024

Created by savemalaysia | Jun 01, 2024