Screen time has increased by as much as 500% during the pandemic, but should parents panic?

Tan KW

Publish date: Wed, 07 Jul 2021, 11:08 AM

Angelina Vicknair had hit a breaking point with her 10-year-old.

Before the pandemic, Jude, a temperate kid, had enjoyed evenings of baseball. But by last summer, he was having nearly nightly meltdowns after burying himself deep inside the virtual world of video games.

Like many parents, Vicknair had significantly relaxed screen time rules during months of remote school, turning a blind eye to the long hours spent staring at computers or feverishly playing on gaming devices. She and her husband had to work, her son’s social life had migrated online, and behavioural experts were advising that it was OK to tailor new routines to survive Covid-19.

But, she said, it got to a point where she could no longer ignore repercussions of the looser restrictions for Jude, and for his seven-year-old brother, Elijah.

“My husband and I noticed that with both children, it significantly altered their personalities,” Vicknair said of the nightly hour of gaming following months of six or more hours spent staring at a computer screen for school. “It impacted him almost like a drug in that way...and that frightened me when I saw that.”

Now, 16 months after the pandemic shuttered much of Louisiana, Vicknair, a Belle Chasse resident and spokesperson for the media company New Orleans Mom, is among the many parents struggling to get their kids to unplug.

And it’s not just in south Louisiana, where summer heat and rain contribute to increased television and digital device usage during normal times. Blogs and social media sites show caregivers all over grappling with kids who want to stay tethered to screens even where in-person social life is opening up.

Plenty argue about the pros and cons of screen time, and there’s not consensus among experts about just how dangerous it can be. But data shows an undeniable surge in usage, with a staggering number of families significantly increasing consumption.

Roblox, a popular gaming app that Vicknair’s kids use, saw a 95% increase in daily users by the end of 2020, from 17.1 million to 33.4 million. A survey done by Parents Together, a family leave and education advocacy group, found nearly half of the respondents’ kids were spending more than six hours each day online, a nearly 500% increase from before the pandemic.

The data contrasts wildly with American Academy of Pediatrics advice, which recommends that children younger than 18 months get zero screen media other than video-chatting, and that children ages two to five years get less than two hours a day of high-quality programs. For older kids, the doctors recommend creating “consistent limits”.

But should parents panic? Have families who have allowed as many as 40 hours a week of screen time during much of the past year somehow damaged their children?

No, according to Dr. Lee Ann Annotti, a licensed psychologist who specializes in Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychology at Ochsner Health System.

“Parent guilt is real, and it is hard,” Annotti said. “But what was your priority last year? It was keeping your child safe by any means possible. And parents did it.”

However, she also cautioned that “we are in a new time” in the pandemic, when parents should now start to think about how to wean kids off of screens to do more activities missed last year.

She reported seeing more kids now for severe tantrums, meltdowns, emotional dysregulation, and sleeping problems, which she said can be caused or exacerbated by too much exposure.

Over the long term, she said too much screen time can negatively affect language and regulatory skills because video games and devices provide instant gratification and delay the mind’s executive functioning, which strengthens when children learn how to problem-solve when stressed.

“It can change the wiring of the brain,” Annotti said.

Her advice aligns with early reporting out of the US National Institute of Health’s US$300mil study on children’s brains and cognitive development, which is so far the biggest long-term investigation into how screen time like game-playing and texting affects kids’ behaviour and development.

The study, which started in 2016 and is tracking more than 11,000 children, has so far indicated that some nine- and 10-year-old kids who spend more than seven hours a day on devices showed thinning of the cortex of the brain, which processes sensory information.

Advice and studies like those are one reason why Jennifer Gonzalez, an English teacher and St. Bernard resident, has not bought a single device for any of her five children, ages five months to eight years.

Her rules changed during the pandemic when the kids had to borrow iPads to do schoolwork, and she eventually let them play games. But now, she said, those have been returned, and all that’s left is a single PlayStation that used to belong to her husband.

“We use it as a reward system now,” she said.

Other parents worry, too, but say they’ve also found some positives to screen time.

Nadine Wu, who said she learned English in part from Sesame Street, let her five-year-old, Nicolas, watch a considerable amount of YouTube during the height of the pandemic, but she played some programs in her native Chinese and French.

“It wasn’t entirely bad,” Wu, a New Orleans resident, said. “He taught me the word for T Rex in Chinese...he learned that.”

Experts have pushed back on some social media-fuelled hysteria over screens, too.

Dr Michael Rich, a child psychologist who runs the Digital Wellness Lab at Boston Children’s Hospital, rejects the notion that screens are addictive, because he says taking them away doesn’t trigger physiological responses, like getting sick. And though the brain is changed by screens, it’s not yet fully understood what that means, he said.

Rich pushes that the conversation shouldn’t be about screen time, but about screen behaviour. He encourages “the three M’s” - mentor, monitor, and model - which means being present for kids even while they play their games.

“The science has shown it’s not the amount of time you spend on screen, it’s what you spend the time doing,” he said. “We’ve been seeking a binary answer to a complex question.”

Others advise that media like PBS Kids and Sesame Workshop are made with child development in mind, while games promoting violence are discouraged.

Annotti points to the Family Media Plan, created by the American Academy of Pediatrics. It advises having screen-free zones in certain areas like bedrooms and setting device curfews ahead of time.

Lisa Philips, a social worker with The Parenting Center at Children’s Hospital, agrees. She suggests letting older kids have “buy in” in part by choosing activities they can do instead.

Vicknair has now found her own happy medium for her kids by allotting screen time in one-hour sessions on Wednesdays and some on weekends, as a reward for doing chores.

And while her youngest still shows some resistance when asked to put Minecraft away, playing it at least convinces him to take out the trash and clean his room beforehand, she said.

“It’s good because it’s been a motivator for him,” she laughed.

- TNS

More articles on Future Tech

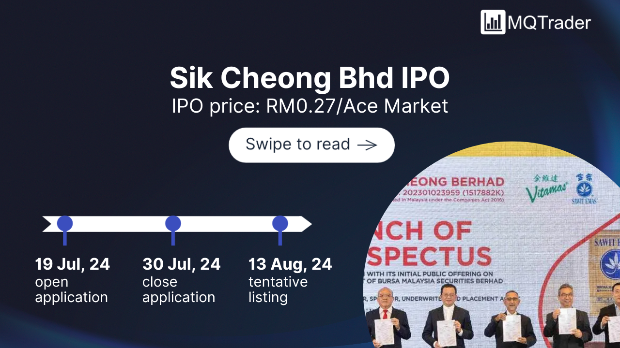

Created by Tan KW | Aug 11, 2024

Created by Tan KW | Aug 11, 2024

Created by Tan KW | Aug 10, 2024