Drowning in code: The ever-growing problem of ever-growing codebases

Tan KW

Publish date: Tue, 13 Feb 2024, 07:19 AM

FOSDEM 2024 The computer industry faces a number of serious problems, some imposed by physics, some by legacy technology, and some by inertia. There may be solutions to some of these, but they're going to hurt.

In a previous role, the Reg FOSS desk gave three talks at the FOSDEM open source conference in Brussels. In 2023, I proposed one under the banner of the Reg, so some of the points hearken back to earlier articles. Unfortunately, since submitting the proposal in October something sad happened, even if it was inevitable. A giant of twentieth century software design, Niklaus Wirth died. As a small tribute, I decided to change the way I introduced this talk.

Wirth is famous for one thing, but arguably, it wasn't the biggest aspect of his career. To pick a superficially small but pervasive example: the computers Unix was written on used teletypes as their terminals. These were, very roughly, printers with a typewriter keyboard on them. Teletypes are why Linux console device files are called tty.

Typewriters have a shift key, and often not much else. But computer keyboards have lots of modifier keys: Control and Alternate (or "Option" or "Meta") and Super (or "Command" or "Windows"). The bits in memory which represent if one of these are pressed down are called Bucky bits… Because Niklaus Wirth studied in, and taught in, and loved, California, and his nickname there was "Bucky".

Bucky Wirth didn't just invent Pascal. Pascal grew out of a proposal to improve Algol. The Algol committee turned it down and picked someone else's, more complicated, idea instead. That became Algol 68 and killed the language forever. As a result, we got other languages that were the indirect offspring of Algol: which took Algol's ideas and changed them. Languages such as BCPL, which was turned into B, which became C - and C++ and everything built from them.

All because the Algol guys didn't like Bucky Wirth's simple, clean, proposal. Wirth went on to create Pascal. This was a big hit. A large part of the Apple Lisa operating system was implemented in Pascal, and that went on to profoundly influence the Mac. A Unix was implemented in a Pascal dialect, too. It was called TUNIS: the Toronto University System, and it was written in a Pascal derivative called Concurrent Euclid.

Pascal became Turbo Pascal which became Borland Delphi and drove the success of Microsoft Windows 3. Delphi was, for a while, huge. But Wirth ignored all that and went on to write a successor, called Modula. Then he threw that away and wrote a successor with built-in concurrency called Modula-2.

Late in Wirth's career, he became a passionate advocate of small software. He wrote a wonderful short article about this. It's called A Plea For Lean Software [PDF], and it's only a few pages long. Read it. It's worth it. It won't take long. As a proof of concept of the validity of the concept, Wirth moved on from Modula-2 and wrote his masterpiece, Project Oberon. Oberon is a tiny Pascal-like language, with concurrency primitives. But it's also a compiler for the language, and an IDE for it. That IDE is also a tiling-window based OS in its own right. For the obituary I wrote for Prof. Wirth, I downloaded the source code of the core of Project Oberon and ran a line count. It comes out a bit over 4000 lines. Specifically, some 4,623 lines of code, in 262kB of text.

That's a self-hosting bare-metal OS. It is unbelievably tiny.

Debian 12, for comparison, is 1,341,564,204 lines of code. That's the project's own estimate. One and a third billion, that is, one and a third thousand million lines of code. For comparison, Google Chrome is about 40 million lines, which is in the same ballpark as the Linux kernel these days.

Nobody can read the source code of Chrome. Not alone, not as a team. Humans don't live long enough. Any group that claims to have gone through the code and de-Googlized it is lying: all that's possible to do is some searches, and try to measure what traffic it emits. A thousand people working for a decade couldn't read the entire thing.

This is the sort of size of codebase that we are building the internet from these days.

These projects are so incomprehensibly vast that no human mind can comprehend even one small isolated subset of the entire thing.

We consider this normal. Everything is like that. It's just how it is. Computers are big, storage is cheap, interconnects are fast, and it works and it scales and it is all pretty amazing compared to the systems I started working with.

A hobby of mine is trying to clearly define some of what I call the Big Lies in computing. In 2022 I wrote that you can't buy software. That means you, the reader, can't. Cash-rich multinational corporations absolutely can buy software, and they often do. But mere users can't. All we get are licenses that say we own the right to use one copy, or if you own a business, so many copies… and anyway, you don't get the source code, or any kind of guarantee.

That, of course, is why Free Software has done so well. If only big companies really own software then the only remaining choice is software that nobody owns and nobody controls and that's built and maintained by its community of users. That's why FOSDEM exists.

So, let's move on to another big lie:

Computers aren't much faster now than they were a decade ago, and they will probably never again return to the rate of performance improvement they had for 60 years up to the mid-noughties.

Moore's Law is over, replaced by Koomey's law. Now, computers use less electricity, emit less heat, and they continue to get smaller and cheaper… but they're not getting massively faster the way that they did in the 20th century. Many Reg readers will remember the Pentium 4, Intel's space-heater chip launched in 2000, and which the company planned to ramp up to 10 gigaHertz by 2005.

It didn't happen. We got the smaller, cooler-running Pentium M instead, which evolved into the Core, Core 2 and then Core i-thingy ranges today. And thanks to AMD, they are 64-bit now. What we got instead of much faster processor cores are more processor cores.

The thing is, that doesn't scale very well. On the desktop we have four-core machines and now we're moving to eight-plus cores, but a single person can't use that very helpfully, so instead, we're getting computers with a mixture of high-performance but hot, power-hungry cores, and lower-performance, cooler, but more electrically-efficient cores.

As Sophie Wilson, co-creator of the Arm chip, observed, the silicon chip industry is very good at finding ways of selling more and more products to us that we can't use because they must spend ever-increasing amounts of time turned off and not doing anything - or the device will incinerate itself.

Server chips have lots more cores, of course, because servers can use that better, but that has a ceiling too. Look it up: it's called Amdahl's law, after the late great Gene Amdahl, and it's quite scary. Even if a program can be made 95 per cent parallel, the maximum speedup you can get is about 20 times, no matter how many processor cores you throw at it.

Once we started to get multi-core processors, Moore's Law meant that the transistor budget was spent on getting wider, not faster. Now we are getting built-in dedicated silicon for rendering 3D graphics, often disabled in favour of more powerful off-chip rendering silicon. Silicon for matrix arithmetic. Hardware dedicated to accelerating certain cryptography algorithms. Silicon for modelling neural networks for so-called "AI" features. ("AI" is another big lie, but one I won't go into here.)

These CPU components aren't the only bits that are getting faster: computers' other subsystems are improving, too. Memory is getting faster. Solid state storage is getting faster, although as I wrote last year, the most exciting kind of non-volatile memory - a bold attempt to bypass a whole pile of legacy bottlenecks and move non-volatile storage right onto the CPU memory bus - flopped. It was killed by legacy software designs.

All this stuff helps certain specific functions, but it doesn't make your general programs go faster.

In the mid-1990s, for one of the UK's leading computer magazines, I ported their in-house benchmark suite from 16-bit Windows to 32-bit Windows. I do know a little about benchmarking. Benchmark vendors now include tasks like video compression in their tests, even though most computer users never do that, just because the benchmark-sellers need some way to test the performance of multi-core chips. Multicore processors do manage to execute some stuff faster, and benchmarks need to show that.

These performance numbers aren't lies, exactly… but they are no longer relevant to ordinary desktop or laptop computing. Nor, mostly, are they relevant to server computing either.

So, yes, computers are still getting a little bit quicker every year and a half… but the thing is that up until about twenty years ago, they doubled in speed that often. Now it's a mere ten or 15 per cent. Unfortunately, our worldwide computing industry evolved to fit a market where microprocessors just kept getting faster, which they did, consistently, for about thirty years.

This industry is, by nature, unable to adapt to a world where that no longer happens - and never will again. The result is spiralling software bloat. Even the IEEE says so. The industry is profitable because most of this software is in unsafe programming languages, or marginally safer ones that are implemented in unsafe languages… resulting in a teetering stack of dozens of layers of flakey unreliable code, which in turn needs thousands and millions of people constantly patching the holes in it, and needs customers to pay to get those fixes fast, and keep paying for them for years to come.

The world runs on software, produced and consumed on an industrial scale, always getting bigger and more complicated.

Nobody understands it any more. Nobody can. It's too big. But it's the only model of making and selling software we have, so we are trapped in it.

And, because computers aren't getting much quicker, as it gets bigger, software is getting slower. That's why we're not seeing big exciting new features, new capabilities and tools.

Thanks to Koomey's Law, as we reach a quarter of the way through the 21st century, even pocket devices can throw around high-definition video streams. Thanks to vast server farms, they can understand speech and natural language… kinda sorta. But they can struggle to recognize our faces, and cannot read expressions or tone of voice. We can't mix speech with other UIs, and it's been so long since we standardized UI design that we've forgotten how to do it.

As a result, we have some big problems in this industry, and we are not confronting them. Software is vast, and vastly complicated, and nobody can adequately understand it all.

It is too big to usefully change, or optimise. All we can do is nibble around the edges, removing bits here, making other bits a bit faster. It's almost fractal, so there are a near infinite number of edges to nibble at… but it's still getting bigger, so the problems are getting harder all the time.

This also means we can't check the whole thing. It's too big. All we can do is have a lot of people watching it for when it goes wrong, try to trace what happened, and fix that symptom.

Computers are getting more parallel. But, as far as anyone knows, it is simply impossible to automatically take algorithms and parallelise them. Only a human mind can do that, and yes, usually, it is a mind, in the singular.

That means that only chunks that can fit into one mind can be refactored like this.

This level of bloat is a crisis that Wirth foresaw when it was one per cent of today, when Windows 95 fit onto 13 floppies, and what he pleaded with the industry to consider and address.

There is an urgent need for smaller, simpler software. When something is too big to understand, then you can't take it apart and make something smaller out of it.

You can trim it a bit, but to make profound changes, you have to go back to the planning stage, reconsider what you need, throw away what you don't, and try to make some minimum viable product that does the essentials and nothing else.

This is the existential crisis facing the software industry today, and it has no good answers. But there may be some out there, which is what we will look at next.

Bootnote

This article is extracted from part of the author's talk at FOSDEM 2024 in Brussels, which was titled One way forward: finding a path to what comes after Unix. The other parts will follow soon. ®

https://www.theregister.com//2024/02/12/drowning_in_code/

More articles on Future Tech

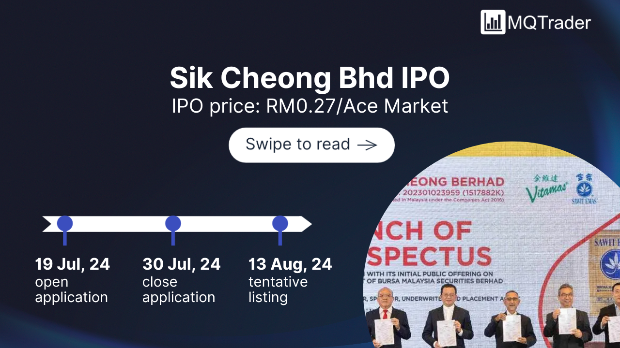

Created by Tan KW | Jul 30, 2024

Created by Tan KW | Jul 30, 2024

Created by Tan KW | Jul 30, 2024

Created by Tan KW | Jul 30, 2024