GEORGE TOWN: Over the past 20 years, Penang has lost a whopping 100 hectares of its mangroves — equivalent to 100 football fields — due to various reasons, but mostly to unmitigated development.

The majority of the destruction, however, took place in the last 10 years alone.

The Penang Inshore Fishermen Welfare Association (Pifwa), which had been spearheading the planting of mangroves since 1997, said the state's forests had declined sharply over the years, with the shrubs that bloomed in coastal inter-tidal zones no longer visible in many areas, both on the island and on the mainland.

Pifwa president Ilias Shafie said now, mangroves could be found only in certain places in Balik Pulau, in the southwest district, and from Juru to the Perak border in Seberang Prai Selatan.

"Besides unmitigated development, Penang is also losing its mangroves to pollution, especially from industries, prawn farming, eateries and housing.

"A sizeable amount of mangroves were also lost to reclamation and erosion.

"Altogether, we have seen the destruction of about 100 hectares of mangroves since we first came into the picture until the present day. There used to be about 300 hectares of the mangroves back then. Now, we only have about 200 hectares left.

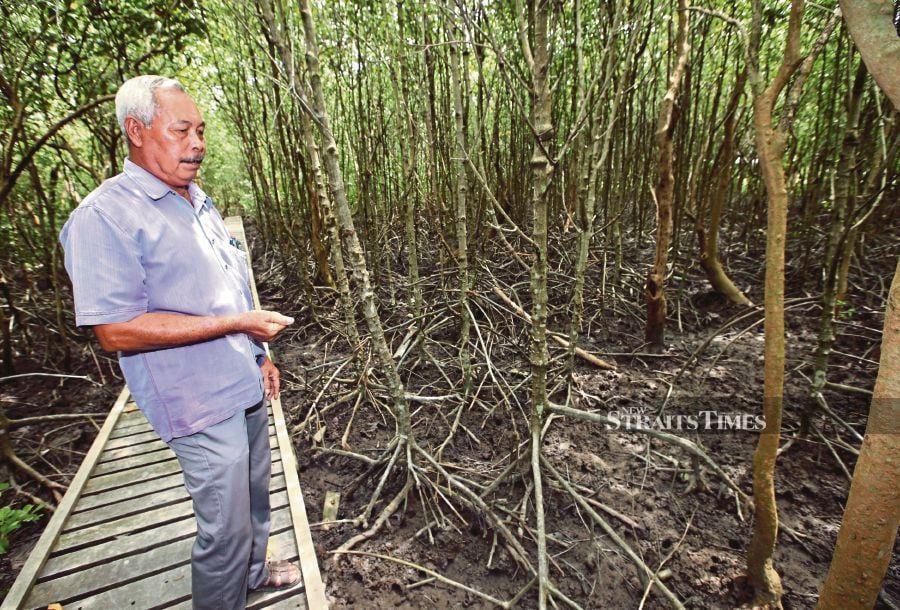

"If this situation continues, we fear that our future generation will never know what mangroves are," he told the New Straits Times in an exclusive interview at the Pusat Pendidikan Kecil Hutan Paya Bakau in Sungai Acheh, Nibong Tebal, recently.

No official data were available on the amount of mangrove forests on state land.

Most of the destruction happened on state and private land, and did not include permanent forest reserves.

Ilias said mangroves were no longer suitable to be grown in Seberang Prai Tengah due to coastal erosion, and in Seberang Prai Utara due to sand waves.

He added that on the island, there used to be mangroves in Gurney Drive, but not anymore.

"Similarly, the Koay Jetty, a former fishing village, used to have beautiful mangroves back then. Now, there is nothing left to remind the present generation of the past.

"The same goes for Batu Maung, Tanjung Tokong and Batu Ferringhi. The only area on the island with mangroves is Balik Pulau," he said.

Previously on the mainland, tracts of mangroves could be found from Prai to Penaga.

"However, no thanks to reclamation and erosion, the mangroves have greatly dwindled, leaving only some stretches in the Penaga area.

"In Penaga, an area near the mangroves have been earmarked for prawn farming, but was stopped at the 11th hour after migratory birds were seen visiting the area. We voiced our objections and managed to save some of the mangroves there.

"In Batu Kawan, about 80 per cent of the forests had been destroyed, while in the case of the Byram Mangrove Forest Reserve in Mukim 11, Seberang Prai Tengah, where century-old mangroves were once abundant, the majority of the forest had been destroyed due to leachate spillage.

"Such a situation is not only prevalent in Penang, but also in neighbouring Perak and in Merbok, Kedah, as well," he added.

According to Ilias, the small patch of mangroves that could be seen as one entered and exited the Penang Bridge and Sultan Abdul Halim Mu'adzam Shah Bridge from the mainland "is merely for show", and might not even meet the 500m buffer zone required from nearby developments.

Even then, he said a 1km buffer was more appropriate to ensure serious protection of the mangroves. Ilias said, of the approximately 350,000 mangrove saplings that Pifwa had planted since 1997, they were only about 200,000 left now.

"Nevertheless, we still continue to plant them despite the destruction. Look at it this way... if we don't plant the mangrove saplings, then we risk losing our mangrove forests in the next few decades.

"If we plant them, although some may be destroyed, there will still be mangrove forests available for the future generation," he added.

Ilias said with Prime Minister Tan Sri Muhyiddin Yassin's recent unveiling of the Malaysian Forestry Policy, this gave hope for greater protection and conservation of the forests, including mangroves.

"We see hope there. Hopefully, this will mark the end of further destruction of the mangroves," he added, pointing to the fact that mangroves were important to the coastal ecosystem.

When the tsunami hit parts of Asia including Penang in December 2004, mangroves had helped to buffer its destructive impact, and this had spurred various quarters to implement programmes to plant saplings.

The mangroves were also beneficial to the ecosystem, such as for fisheries, coastal protection and sediment accretion, carbon sequestration, silt reduction in rivers, bioremediation of waste and nature-based tourism.

On his part, Ilias said the association had planted about 8,000 to 12,000 mangrove saplings annually. This year alone, they had planted 4,000 saplings and had received requests for some 30,000 more.

At the Pusat Pendidikan Kecil Hutan Paya Bakau, there were about 13 species of commercial mangroves grown at its nursery.

Among them, Ilias said, were the Bakau Minyak and Bakau Kurap, which were near extinction.

"When we first set up the centre, we found that there were few than a handful of trees of both species left.

"And then, when we talked to the locals, they told us that the area used to be populated with the two species.

"We set out to grow them and now, we have about 2,000 trees. We can say the species are now stable," he added.

There were nearly 50 species of mangroves altogether. However, only 30 species were grown together at any one place.

The centre usually received sponsorships and visits by representatives of companies and people to plant the mangrove saplings. However, all that stopped since the Movement Control Order was imposed last year.

Now, Pifwa had come out with its own funding to sustain its operations, and utilises its own volunteers to plant saplings.