Is Travel and SOP Easing Now a Good Move?

Ben Tan

Publish date: Sat, 20 Feb 2021, 03:27 PM

A hypothetical business manager is provided with two options, and with these two options only, by the government of their country:

Option A: Close your business now, for 3 months. We will foot part of your ongoing operating expenses. Once the 3 months period is over, you can reopen your business and you will most likely not have to close it again.

Option B: Close your business for 1 or 2 months. We will foot part of your ongoing operating expenses. Once the 2 months period is over, you can reopen your business. However, there is the chance that you may need to close your business again a few months later for another 1 or 2 months.

Remember - these are the only two options the business manager is given. Which one of these options do you think a sensible business manager would choose? In the vast majority of the cases, the business manager will choose Option A. Why? Because uncertainty is the biggest enemy of every business manager. The more uncertainty there is, the more difficult it is for a business to make and execute on any plans, as even the most basic things such as short-term sales projections become unknown.

Early on the Malaysian government took some very prudent measures to control the COVID-19 pandemic within the country. The first lockdown (started on 18 March 2020) allowed the Ministry of Health to track down and clusterize infected individuals and their contacts. The country effectively closed its borders, which prevented import of new cases. Most days in the 3-month period between June and August 2020 there was only a single-digit increase in cases, and in most cases when the increase was double-digit that was because of imported cases (i.e. cases screened on arrival from overseas).

Things started breaking down when on 1 September 2020 the Lahad Datu cluster in Sabah was discovered (source). In the period between 5 June and 6 September, most cases in a single day were recorded on 13 June - 43 (source). However, since 6 September only on five occasions there have been fewer positive cases in a single day - on 9, 14, 15, 17, and 19 September (source, source, source, source, source). Additionally, 30 September 2020 was the last day when double-digit cases were reported in the country (source). Malaysia was unfortunate enough that the detention center cluster (which had spread into the community) happened in Sabah exactly when the Sabah state elections were taking place (on 26 September).

I just want to make it clear that I do not think the Malaysian government is to be blamed for this. As we saw after the announcement of the Darurat in January and the resulting postponement of the general elections in the country, even with thousands of cases per day, people were unhappy and conspiracy theories arose, blaming the government for playing dirty games. Now imagine what the response would have been if the government had postponed the Sabah state elections with "only" double-digit cases per day (average of 50 cases per day between 1 September and 25 September, the day before the elections). The government simply didn't have a right move in that situation. It was an unfortunate coincidence which resulted in an exponential increment in cases and a broad community spread, starting in Sabah and Selangor, before moving on to other states.

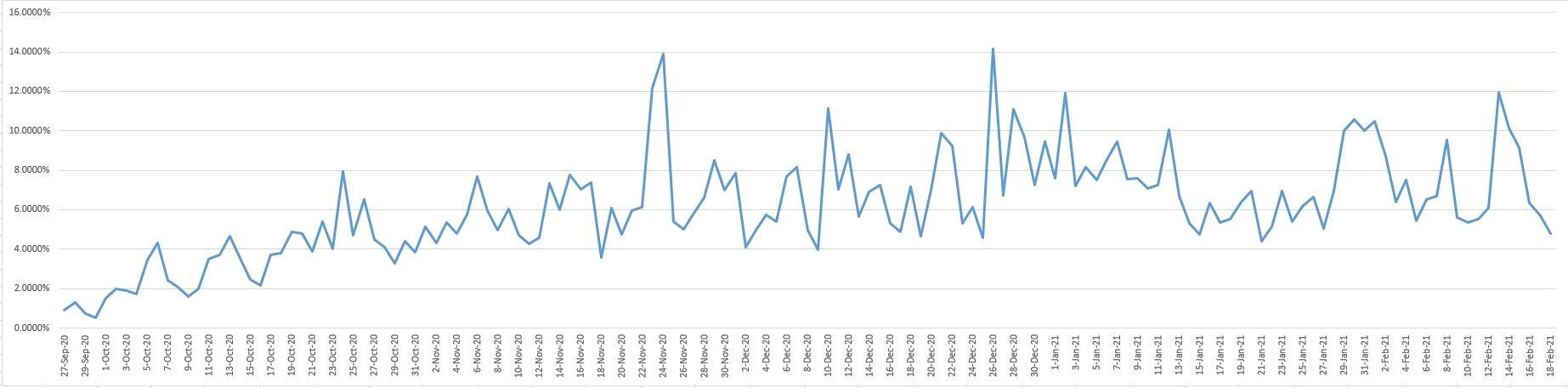

On 12 October 2020, conditional movement control order (CMCO) for Selangor, Kuala Lumpur, Putrajaya, and Sabah was announced (source). It included tight inter-district and inter-state movement restrictions. At that time the average number of cases per day was still relatively low compared to what we are observing nowadays - 416 new cases per day on average between 1 October and 12 October. More importantly, the positivity rate was also much lower than the currently observed - 2.40% on average (more on how I extract this data later).

While these measures slowed down the spread of the infection, they didn't stop it. Between 13 October and 4 December the average number of daily cases was 1,019 at 5.57% positivity rate. For the two weeks before 5 December, the average number of daily cases was 1,257 at 7.08% positivity rate. Unfortunately, and albeit this, the government decided to ease the restrictions, announcing on 5 December 2020 that interstate travel would be allowed once again starting from 7 December 2020 (source).

Based on this data, it should have come as no surprise that only a few weeks later, on 11 January 2021, a nationwide movement control order (MCO) was imposed (source). Between 8 December 2020 and 10 January 2021 the average number of daily cases increased to 1,815 at 7.67% positivity rate. In the two weeks before 11 January, the average number of daily cases was 2,207 at 8.58% positivity rate.

Over the last few days, the government started easing up some of the restrictions. From 19 February, most states move to CMCO regime, while the MCO remains in power only in Selangor, Kuala Lumpur, Penang, and Johor (source). Unfortunately, based on publicly available data, these measures might be premature at this time. There are a number of signs pointing to that:

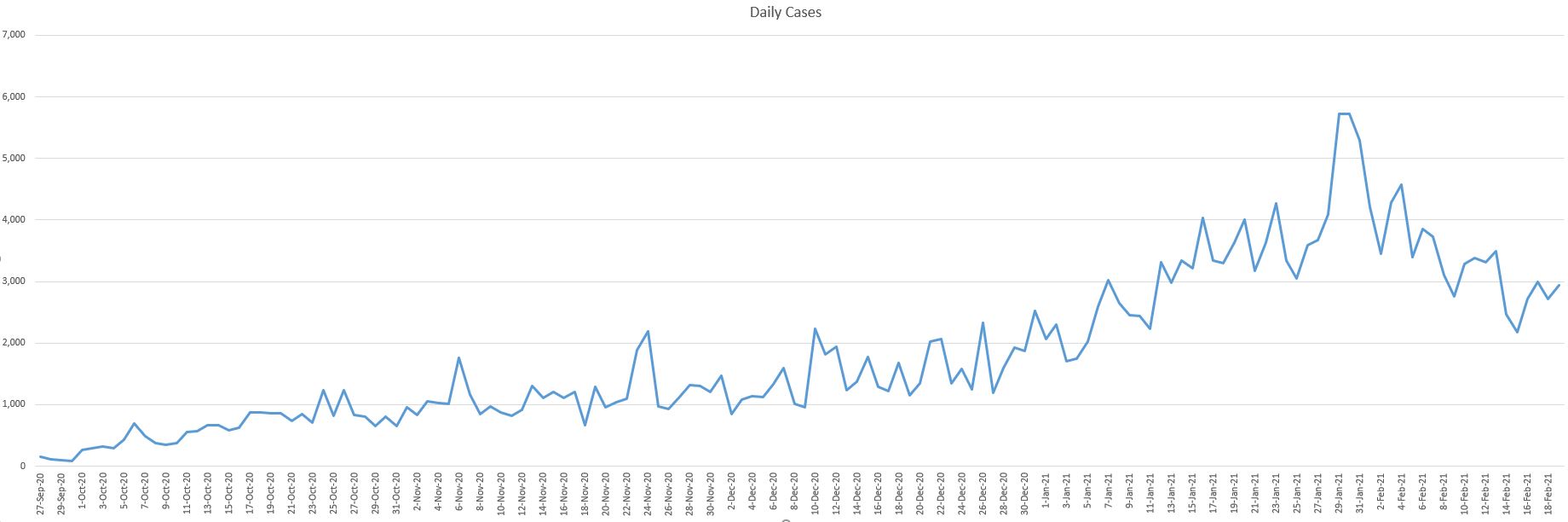

1) Number of Cases

While most people focus on this as it is the easiest to understand factor, this is also the weakest factor of all people frequently use to get guidance on where things are heading. Daily cases can vary greatly based on number of tests conducted/processed on a given day. Thus, this factor cannot be reviewed in isolation. Having this in mind, over the past 1 week, the average number of daily cases is 2,786. This is still more than the average for the week preceding the MCO announcement - 2,416 cases on average.

The only time the daily cases dipped over the past few weeks was on 14 and 15 February when the daily tests processed were a lot fewer than on any other day. This resulted in a significant spike in test positivity rate as we will see later.

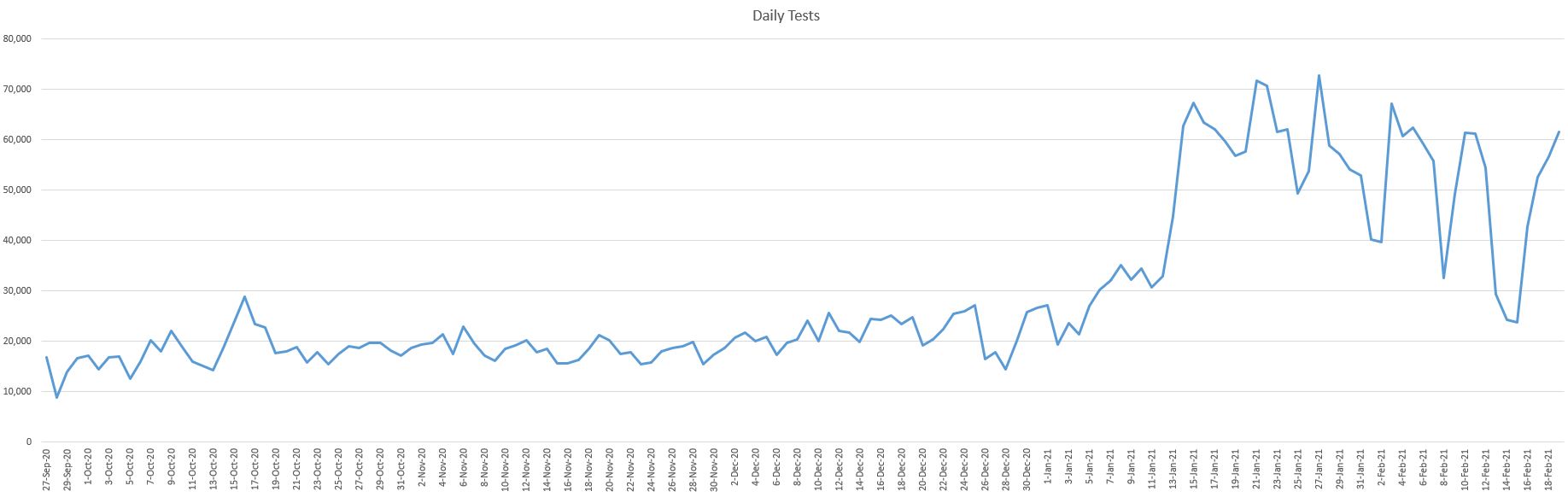

2) Positivity Rate

This is a much more accurate determinant of the situation, because it takes into account how many tests have actually been performed. The positivity rate for the past week was 7.55%. This is slightly lower than the positivity rate in the week before the announcement of the MCO - 7.98%. However, this lower positivity rate is achieved at more tests conducted - 41,574 per day for the past 1 week compared to 30,344 per day on average for the week before the announcement of the MCO, i.e. the lower positivity rate comes at 37% more tests conducted. As tests are conducted among the broader population, it is expected that (hopefully) the positivity rate will decrease. Unfortunately, the decrease is not significant. The positivity rate is still staying at a pretty constant level, even compared to November and December when significantly fewer tests were being conducted.

3) New Clusters

This is probably the most worrisome factor. For the entire period of last year, in total 514 clusters were detected in the country. Of these, 152 were reported in December alone. However, in January 306 new clusters were reported (10 per day on average), and so far in February 241 clusters have been reported (13 per day on average). This increase in discovered clusters since December is of course partially related to the increased amount of screening since the beginning of 2021. However, it signifies that there is a significant number of hidden community transmissions. A new cluster simply means that no origin of the infection can be established in association with a known cluster. This is very dangerous because it means that diffusion spreading is observed, instead of clustered spreading. Malaysia's testing strategy was tailored towards containment and origin tracking since the very beginning. That is how the country was able to contain the number of cases while conducting relatively few tests. However, this strategy cannot work anymore since tracking of origins currently appears beyond the human resource capabilities of the Ministry of Health. Thus, the only way forward may be much broader testing. Unfortunately Malaysia is still ranked 104th in the world in terms of tests per 1 million population (source).

A reminder that after the allowal of interstate travel on 7 December 2020, it took only 35 days before nationwide MCO was declared. The easing in December happened at positivity rates lower than the positivity rates observed at present and in a period when much fewer active clusters existed. In this case, any quicker than needed further easing of the measures might result in problems down the road - sooner than we might wish for.

Note on Data

The Ministry of Health (MoH) doesn't publish daily figures on positivity rate and on daily tests. However, the MoH publishes daily cases figures and statistics on "overall tested individuals" every day. Based on this data, we can extract how many new tests have been conducted/processed for the day, and then we could use it to calculate the day's positivity rate.

Important disclaimer: Any views expressed are for informational and discussion purposes only. None of this information is intended as, and must not be understood as, a source of advice. It is imperative that you always do your own research and that you make any decisions based on your personal situation and your own personal understanding.

More articles on Trying to Make Sense Bursa Investments

Created by Ben Tan | Jun 04, 2021

Created by Ben Tan | May 09, 2021

Created by Ben Tan | May 04, 2021

Created by Ben Tan | May 01, 2021

Discussions

Hi observatory, thank you very much for your comment and thoughts.

The goal of my article wasn't really to discuss the government response in detail. In fact, I tried to avoid that topic in the article as much as possible, so I didn't elaborate on the Sabah elections or on December's interstate travel ban lifting. Overall, my goal was to demonstrate that lifting the restrictions right now is most likely not a good idea and that it will result in deeper problems soon. Additionally, it was my goal to show that, unfortunately, things have not been improving ever since the end of September, albeit all the imposed restrictions. This makes me quite concerned about the situation in Malaysia, and in my view the near-term prospects for the economy as a whole are bleak.

Regarding your points, I agree with all of them. There have been significant shortcomings in the way the government reacted to certain situations, but unfortunately without knowing all the facts that might have been taken into account, it may be hard to judge. Comparing the situation in Malaysia to that elsewhere in the world, we can clearly see that Malaysia is even now still doing better than most other places. A few countries, such as Singapore, Brunei, Taiwan, Mongolia, New Zealand, and Australia, are certainly doing better, but they have significant advantages over Malaysia - in particular remote location, and/or small enough size, and/or are thinly populated. Another, smaller group of countries, including China and Vietnam, is doing better as well, but they have the "advantage" of being totalitarian states. Malaysia's major strategic disadvantages in this case have been its proximity to populous countries, such as Indonesia, The Philippines, and Bangladesh, where the pandemic has not been contained, and its large population of illegal immigrants. This is not something the government could have resolved easily.

In this sense, while in retrospect some decisions turned out to be wrong (such as not quarantining people traveling to Peninsular Malaysia back from Sabah in September, for instance), the overall response has been significantly better than average, especially bearing in mind how complicated a political situation the government has been operating in.

But again, the goal of this article was not really to do an overview on the political response, but rather to express an opinion on the situation we are dealing with right now.

2021-02-20 22:21

Hi Ben. I understand your points. I think your assessment of government actions is fair and balanced. As compared to most developing countries and even some developed ones, Malaysia is doing OK. However just like every boss tends to be demanding, sometimes unreasonably so, I hope Malaysian politicians will feel the heat from citizens demanding the best from them. Such pressure is necessary for the country to progress.

If I read your blog correctly, you seem to favor another one-time, longer, stricter lockdown to bring the cases down to near zero or really low level before reopening. One-time pain is better than prolonging the limbo state, which is the danger of premature relaxation.

This in fact is the China approach. Whenever there is a small outbreak of maybe just a few cases, the whole neighborhood will be under strict lockdown and the entire city population is tested within days. As a result, Chinese citizens could confidently carry out their normal activities despite their vaccination rate of only 3% of the population. So long as they continue to shut their borders, they are fine.

Unfortunately, I don’t think Malaysia could adopt this model even if the strict MCO 1.0 version is imposed for another 2 months. Unlike Mar last year, the virus has taken root in every corner. There are too many asymptomatic carriers that which is like a hidden fire burning underground of peatland. They could not possibly be flushed out without a Chinese-style whole of the city kind of mass testing. Malaysian simply does not have the manpower, organization and political will to deliver that. Outside of China, the only near success I read is Slovakia which tested 3.6 million out of 4 million population in last Oct. But even their mass testing only served to halve daily cases from 2K to 1K before bouncing back the next month.

Even if Malaysia could successfully carry out the mass testing and flush out every carrier (not an easy feat given there could be false negatives in testing), the viruses could soon make come back through the porous borders as you’ve mentioned. If unchecked, the strict nationwide lockdown earlier could simply go wasted, easily at the cost of another 5% or so GDP contraction.

The repeated flare-up is also the experience for advanced East Asian economies. Korea, Japan, Taiwan and Hong Kong all have seen the periodic resurgence of cases. So Malaysia has no choice but to make a fine balance between opening up and containing the pandemic. Without the Chinese advantage, it has to follow the Western approach of rapid vaccination rollout strategy. The latest vaccination progress chart I read (as of Feb 16) shows Israel at close to 80%, Britain above 20% and US at 17%. Large scale study in Israel has shown the vaccines has made a significant positive impact. Daily cases are declining fast in UK. Can Malaysia learn something from these countries on how to roll out their program faster and effectively?

Put all focus and resources into a successful vaccination rollout. Up the budget if necessary. Even assumed at RM 500 per person (an average dose probably costs only USD20 or RM80), it will cost the nation merely 33 million * RM500 = RM16.5 billion, which is just about 1% of 2020 nominal GDP at RM1,341 billion. The cost-benefit equation is a no-brainer.

While vaccines may not fully protect individuals from contracting Covid-19, they can significantly reduce severe cases. By driving up vaccination to a rate of say at least 80% in the next 3 quarters, it would have restored a lot of confidence, the necessary foundation for many economic activities.

The 1918 Spanish flu killed at least 50 million (some said 100 million) but it subsided in 2-3 year time without substantial economic damages. That was achieved purely based on natural herd immunity. There is no reason that with much better scientific understanding, medical help and resources at our disposal today, we cannot organize ourselves and do a better job than in 1918.

2021-02-21 00:21

Hi observatory, thank you once again for your detailed response.

My preferred strategy for Malaysia is that cases are reduced by a meaningful amount before any relaxation of the SOPs is imposed. Unfortunately, from a practical point of view it is impossible for Malaysia to reduce the cases to zero, the way China or Australia are doing it. However, finding as many clusters as possible during these movement control order episodes is imperative, so from this point of view the increase in testing by almost 3 times over the past 6 weeks is commendable. Extra budget must be (or rather - must have been) allocated for this task, because the corresponding economic damage from prolonged movement control restrictions far outweighs any costs for extra testing.

In terms of the vaccination program, I actually believe Malaysia has done surprisingly well. I don't necessarily agree that paying a significantly higher premium for getting a few batches of vaccines 1 or 2 months earlier would have changed much. For instance, Singapore has apparently paid 5 times more per vaccine on average than Malaysia. However, they have only administered 4.38 doses per 100 people so far, or the equivalent of 2.2% of the population (if we assume 100% coverage). Malaysia has managed to secure a diverse range of vaccines from different providers, which is imperative having in mind the geographic diversity of Malaysia. Again, setting up this program in a place like Singapore is an infinitely less complicated task than doing it in Malaysia.

Unfortunately, the official figures for the countries that are leading the pack in vaccinations - Israel, the UK, and the US (and the UAE by the way), are quite a lot less encouraging. Israel, the world leader, has administered 82.4 doses per 100 people as of yesterday. This translates into 41.2% coverage. The corresponding figures for the UK and the US are 25.73 doses per 100 (12.86% coverage) and 17.82 doses per 100 (8.91% coverage), approximately 2 months and a half into the campaign.

But back to Israel, they are right now facing a problem I wrote about in the beginning of December - vaccine hesitancy. After a very promising start, and a peak around the end of January and the beginning of February when on average 2.1 doses per 100 people were administered per day, the country saw a sharp decline to 1.1-1.4 doses administered per day, and they are now facing the part everyone has been reluctant to talk about. Once you vaccinate everyone willing out of the adult population, you are still left with a significant group of unwilling people (in some cases this group is over 50% of the adult population - in Russia, France, Poland, for instance), and you are left with the children. So from hereon after Israel has a couple of major issues to resolve:

A) How to "force" the unwilling population to vaccinate.

B) What to do with the children.

The unavailability of a resolution to these two problems at present means that COVID-19 will, unfortunately, not be eradicated. At the same time it poses extra risks. When vaccinated population mixes up with unvaccinated population in an environment where herd immunity (~60-70% for the "old" variant, ~80% for the UK variant and other more contagious variants), the virus is given more opportunities to adopt mutations that escape the immune response generated from the vaccines. This is where a major risk lies right now, and that is why it is much more likely that we will have to have yearly COVID-19 vaccination campaigns than the opposite.

Overall, the vaccination campaign will result in a significant decrease in deaths eventually as it will prevent severe illness (in most cases), which is great because it will allow for a certain reopening of the economies. However, it will not result in a return to 2019 level of normal any time in the next few years, unless miraculously a cure is discovered. International travel will remain complicated, and will likely only be based on bilateral travel bubbles, mass gatherings will be restricted, and I expect that the continent of Africa will eventually become isolated in terms of travel. The virus can mutate more easily in immunocompromised individuals, such as HIV-positive individuals. This is likely the main reason why the South African variant has developed specifically in South Africa where approximately 20% of the population lives with HIV. The fight will be long and arduous, sadly.

2021-02-21 12:41

Hi Ben. Thank you for taking the time to explain. Very informative!

Yes, it’s good that the Malaysian government has secured diverse sources of vaccines. The diversity will reduce the risk of a single point of failure.

After reading your reply, I found that I had misinterpreted vaccination does per 100 people with vaccination rate per 100 people. However, the number cannot simply be divided by two. For example, UK has delayed the second dose from 3-4 weeks to 12 weeks. Therefore the coverage is not 25.73 doses per 100 = 12.86% coverage as you've assumed.

Two days ago BBC put the latest number as “more than 16 million have received at least one does”. That is close to 24% of the UK population at 68 million.

https://www.bbc.com/news/health-55274833

Meanwhile, as of Feb 16, the Israel media reports that the country has vaccinated 4 million or 44% of their population, representing 2/3 of the eligible people.

https://www.timesofisrael.com/two-thirds-of-eligible-israelis-have-received-at-least-1-dose-of-covid-vaccine/

The article also contains hints on how other governments may deal with vaccine hesitancy. It reports that after a recent slowdown, Israel vaccination rate has ticked up again because the government has approved reopening venues and events to only those who have been vaccinated (or previously contracted the virus). Its government also considers mandating workers with high public exposure to be either vaccinated or have a virus test every 2 days. In Malaysia, the government has just announced giving out “vaccine passport”, which could serve as a powerful incentive for students/ workers/ business people who need to travel. In other words, faced with a health and economic emergency, every government is going to roll out all the carrots and sticks to get their people vaccinated.

Furthermore, the share of the unwilling population is a changing number. A key reason for not taking up the jabs is due to the concern of side effects. But when the people around like relatives, friends and colleagues have been vaccinated without apparent ill effects, such vaccine hesitancy will decline. There could also be social or workplace pressure to vaccinate.

The next question is how to deal with children. Last week a trial has started in the UK for children as young as 6 years old. There is a strong motivation to get children vaccinated and get them back to school. Remote schooling has not only been disruptive to learning but has also widened social inequality as children from poorer families suffer disproportionately.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/feb/13/oxford-astrazeneca-covid-vaccine-to-be-tested-on-children-as-young-as-six

In fact close to a hundred Israeli children with pre-existing conditions like diabetes, lung and heart diseases, cancer have already been vaccinated. No side effects have been reported. The Israel findings will be closely watched by other countries.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/feb/13/oxford-astrazeneca-covid-vaccine-to-be-tested-on-children-as-young-as-six

Therefore I believe the challenges presented by these two groups are not insurmountable. As vaccines get progressively rolled out to the larger population, attention will shift to these groups. Sticks, carrots and emergency use will be applied.

Having said that, I agree with you that many industries will not return to the 2019 level soon. Commercial airlines, cruise, hotels, outdoor entertainment are among them. This is not only due to fear of traveling but also the new way of working. Business travel will stay low which is bad news for full-service airlines.

Nonetheless, human society and the economy as a whole will soon learn to live with the virus, which no doubt will keep on mutating as viruses did in the past billion years. We have lived through such experiences. Washington Post has carried an article describing what happened after the 1918 Spanish Flu.

“All those pandemics that have happened since — 1957, 1968, 2009 — all those pandemics are derivatives of the 1918 flu … The flu viruses that people get this year, or last year, are all still directly related to the 1918 ancestor.”

https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2020/09/01/1918-flu-pandemic-end/

It is likely that Covid-19 could evolve into something like seasonal flu, which kills many elderly in every season but is hardly noticed by the general public.

2021-02-21 22:39

Hi observatory, thank you once again for your detailed notes.

Just to make it perfectly clear - I am certain the world will find a way to go through the crisis, there is no two opinions about it. Israel, and of course other countries, will find a way to push through and vaccinate as many people as possible, even if that might require certain heavy-handed tactics to be employed.

However, it seems like a difference in our opinions lies in our estimation of how bad the economies of the world will look like once the major phase of the crisis is over. My firm opinion is that the world economy was in decline at least since late 2018, and it was due for a recession in 2020 anyhow. When the pandemic hit, it further scarred the world economy and left no choice to governments around the world but to take on record levels of extra debt while using every available tool to pour liquidity. There is very little (if any) further space for interest rate cuts, which currently stay at historically record low levels. Velocity of money, which as of 2017 was already at record low level (1.45, at historical average around 1.7) since we've had data on the metric, is now at the stagnation (if not complete halt) level of 1.1, with almost no difference between the level at Q2 2020 and Q4 2020. Additionally, at least since the Global Financial Crisis, the governments of the major countries had to take on record levels of extra debt to fuel further GDP growth (i.e. the public debt growth to GDP growth ratio was at its historical record low before 2020).

All of this means that most governments of the world did not have the sustainable capacity to bridge the gap between the beginning and the eventual end of the pandemic, but they were forced to do it. So I am strongly pessimistic on how quickly the economies of the world will return to the right path, even as they undoubtedly will learn to live with the virus.

Another difference in opinions seems to exist in regards with the danger of the virus turning endemic, similarly to the flu and other coronaviruses throughout human history. You seem to be of the opinion that this will generally be fine. In the long run (3+ years from now), I agree. Unfortunately COVID-19 is, at least at present, a pathogen a lot more dangerous than the common flu the world experiences every year. The reason why things won't be as good as with the Spanish Flu scenario hides in the speed with which COVID-19 mutates, which is approximately 4 times slower than the flu. This makes it harder for a variant of the virus to establish itself, which is less lethal or less damaging to the host (humans). It will take longer than with the flu before this happens.

Regarding the technicalities of measuring how far each country is in its vaccination campaign, the most accurate way to report on that is to find out how many people have been inoculated with one dose, and how many with two doses. If you view it from a healthcare system point of view (as you seem to be doing), the one dose stats itself is more important. However, if you view it from an economic and general vaccination campaign completion point of view (as I am viewing it), you will have to calculate how many doses have been administered, out of the total number of doses that will have to be administered before the campaign is completed. I like to measure it this way, because it is a lot more conservative and it gives us the opportunity to more accurately estimate how fast the vaccination campaign is going and when the vaccination campaign will actually be completed.

2021-02-22 11:28

Hi Ben. It’s always nice to read your opinion on such matters. From your reply, it’s clear that you’ve done a lot of readings and given a lot of thought to them.

Yes, we have some differences in opinions in terms of the threat posed by continuous virus evolution and the impact on the world economy. But it is a difference in degree rather than direction.

First the virus. I believe most developed countries should be able to vaccinate a very large segment of their population by the second half of this year. As mentioned earlier, that means they have to make progress on the unwilling population and children. Yesterday the WHO European Director said he believes the pandemic will end by early 2022. So there is hope that the pandemic will turn into an endemic by then.

But you’re rightly concerned about the speed and uncertainty around the virus mutation. However, countries especially developed countries are much better prepared now. mRNA technology has already been proven. Pfizer boss has also claimed that the technology could be retooled to target new variants in 6 weeks. Production and logistic facilities are already in place to support boosters should it become necessary.

However, I agree the future will be rather bleak for many poor countries, especially war-torn countries where public healthcare systems have collapsed. But from the economic point of view, the poor countries have a smaller contribution to the world economy. The OECD countries are responsible for about half of the world GDP (measured on PPP). Adding in China the weight is close to 2/3. They alone absorb most of the export from Malaysia.

2021-02-24 01:30

This brings me to the next subject on the world economy.

You’ve raised an interesting point about declining velocity of money. I don’t have the world figure, but this phenomenon has been observed in the US for quite some time already. The velocity of M1 has declined since 2008, and velocity of M2 has actually last peaked in 1997! But their relationship with the economic health is complicated. US economy was rather good during most of the period of declining money velocity. This 2015 article discusses about the phenomenon.

https://seekingalpha.com/article/3066146-why-money-velocity-continues-...

Actually, the world economy has faced many threats over the last decade. But most of the risks, except the China-US trade conflict, have receded before 2020. At the start of 2020, the US economy was in a very good health with unemployment at a record low level. US corporation were making great profits. The main source of concern during 2018-20 was the US-China trade war. But the threat is no bigger than some of the earlier threats:

(1) Weak banking sector

Some banks, especially in Europe, has not fully recovered from 2008 crisis. However the banks have become a lot safer nowadays after being forced to take on massive equity in accordance to Basel 3. Todays banks, including Malaysian banks, are generally robust and could take on a lot of stress.

(2) Debt crisis in developed countries

You’re right that debt to GDP ratio has gone up a lot, creating doubt on sustainability and impending debt crisis. There has been concern since 2008/09 on how developed countries could get themselves out of their debt situation. And for Japan, that concern has persisted for at least two decades. But so far no major crisis has occurred, except for Greece, which is a small country. The absence of debt crisis has now triggered a rethink among many economists whether sustainable debt levels are a lot higher than they have assumed, especially for countries that issue debts in their own currencies.

(3) Breakup of EU

There were periodic crisis since 2008 starting with the Greece debt crisis, which later evolved into non-confidence in PIGS countries, and was followed by emergence of Eurosceptic populist parties of AfD, National Front, Five Star Movement and eventually Brexit. But somehow the EU and the monetary union muddled on. In fact the outlook has turned much better today. Brexit has already happened without major impacts, except some managable problems for UK. Covid-19 has forced the EU to take the first step toward a fiscal union by setting up a 750 billion Euro recovery fund to assist countries in need. The risk of an EU implosion is now very low.

(4) China hard landing

Again there have been several rounds of scares. A few years ago it was doubtful whether the total debt to GDP ratio at 270% can sustain. But somehow through many intervention the Chinese government has stabilized the debt level and has also engineered a soft-landing in its overheated property market. Instead of capital outflow the past year has seen foreign capital inflow especially to China bond market, pushing up the RMB exchange rate.

Of course the US-China rivalry remains a source of instability. But under Biden's administration the risk of an escalating trade war between US and China, and in fact between US and other major economies, have greatly subsided.

If there is any worry, the worry has shifted away from a weak economy to an overheated economy. The growing appetitie of China and the expectation of Biden's USD1.9 trillion stimulus package has already sent commodity price rising. But central banks would welcome a temporary pick up in inflation as it will lift the economy out of deflation risks.

So while the future is not cast in stone, the general consensus including from IMF and World Bank is growth will pick up in 2021 and 22. While we can't rule out black swans, the outlook seems on balance on the positive side for me. Of course, the world stock market valuation is another matter as valuation may have run too far ahead due to easy liquidity.

2021-02-24 01:54

Hi observatory, sorry I've missed your comment earlier.

In terms of velocity of money, the current levels in the US are scary. An economy can continue going - "mechanically" or with additional government support - for quite a while, ignoring the signs of slowing, but this cannot remain so forever. And the longer it continues, the worse the eventual end is. A recent historical case in point in this sense is the Soviet Union. The USSR, like China in the 1980s, began to grow from an extremely low level after the Bolshevik Revolution. This, together with the abolition of the bourgeoisie in the country and the confiscation of this social cast's assets, made it look like the country was doing really well up until at least the 1970s. However, the truth was that by the early 1960s the systemically wrongly built economy was gasping for air and was only being driven forward artificially. This is unfortunately what we are observing nowadays with the US, and to a certain extent with the EU. We know how the USSR story ended - its dissolution in the late 1980s and early 1990s led to the greatest destruction of wealth in the modern history of the world, specifically for populations in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. I hope that doesn't eventually happen again with certain major players.

But in a nutshell - factors such as velocity of money and GDP/growth ratio do not work out immediately, especially when the situation is as disastrous as it is right now. The Fed tried to get away from this perpetually low interest rate and sea of liquidity situation in 2017, but by late 2018 it had to revert back to the old trend as the economy started showing signs of crashing.

I think people are too readily beginning to ditch time-tested economic postulates. Every time this has happened in history, things haven't ended well. I wish to be able to hope this time will be different, but history teaches us this would be hoping against hope.

2021-02-28 23:33

observatory

Hi Ben. I see that your analysis has brought you to the Malaysian Covid-19 situation. Thumb up for you! I also happen to have a few opinions on this matter. Let me put forward my 2 cents.

IMHO, the Malaysian government has a mixed record. The right things are like the quick imposition of a draconian lockdown during the MCO 1.0 (started in Mar 2020). The rollout of a bold stimulus package to sustain livelihood and businesses in the face of soaring debts. Taking the Covid-19 threat seriously and listening to health experts instead of dismissing it as flu as Donald Trump did.

Now the bads.

First, Malaysian leaders are slow learners during a crisis (or they’re too consumed by politics?). I can understand a sledgehammer MCO 1.0 (Mar 2020), as most of the world governments also had no clues how best to respond. But MCO 1.0 was extended several times up to 2 months with no finetuning or modification across different states and districts. Surely some flexibility could have been injected at the later part of MCO 2.0 with some experimental gradual openings at green zones.

The rigid MCO approach, such as allowing breweries to operate and then U-turn at the last minute, has caused unnecessary economic contractions. The sharp fall in GDP during MCO 1.0 would later come back to haunt ministers like Azmin Ali, arguing against another lockdown when cases soared by citing unaffordable economic damage. The economy was damaged in the first place because the cabinet only knew how to operate in two-mode – either ON or OFF, but not in between!

Second, the government does not learn from other country lessons. Singapore experienced a mass outbreak at their foreign worker dormitories in Apr 2020 with 4 digit daily cases. Given Malaysia has more foreign workers, and many are in fact undocumented, what have the relevant authorities learned and done between April to Nov when mass contagion first came to light starting with Top Gloves factories at Klang? Why the highly publicized raids by Human Ministry were only conducted in Nov and Dec? As Workplace clusters have now become a norm and dropping out from media headlines, are the authorities still keeping up with their efforts?

Third, leaders not walking the talk. While the Sabah state election had to go on, why the health authorities did not impose quarantine demand on West Malaysia politicians returning from campaigning in Sabah, with the full knowledge that an outbreak was happening at Sabah then? Returnees from Sabah were key contributors to the Covid-19 spread in West Malaysia starting in the Klang Valley. The lax attitude made a mockery of the unnecessary strict MCO 1.0 just a few months earlier. And now certain ministers only need to quarantine for 3 days after returning from selected foreign destinations. I wonder do politicians have higher immunity.

Fourth, the lack of coordination at the middle and lower levels of the government machinery. One year into Covid-19 we still hear different standars during enforcement. Isn’t there an internal review and dissemination process to ensure uniform standards? I’m also perplexed by the ill-defined line separating essential versus non-essential businesses. For example, selling shoes was not allowed during MCO 2.0 but selling televisions (I’ve seen in malls) was OK. When apparel shops were reopened, customers were required to wear gloves. But everywhere I go I don’t see eateries kitchen staff or waiters wearing gloves (higher-end restaurants might be the exception). Do people get Covid by touching contaminated clothes but not when they swallow contaminated food?

The list of grievances could go on but that will risk turning an investment discussion into a political discussion.

Nonetheless, I’m always optimistic that this difficult time shall pass soon given human ingenuity. We and our earlier generations have faced far greater challenges in the past but still bounce back from them.

2021-02-20 18:25