To get this kind of information and other exclusive articles before regular readers, get on the VIP Mailing List today.

“…the phrase “earning power” must imply a fairly confident expectation of certain future results. It is not sufficient to know what the past earnings have averaged, or even that they disclose a definite line of growth or decline.” ―Graham & Dodd, Security Analysis (6th Ed.)

A few thoughts from Graham & Dodd and Marty Whitman about how to think about earnings and how it may differ from earning power.

In The Aggressive Conservative Investor Marty Whitman discusses the importance and implications of distinguishing between earnings and earning power:

Given the varied economic definitions of earnings, it may be wise to distinguish between earnings and earning power. By “earnings” is meant only reported accounting earnings. On the other hand, in referring to “earning power” the stress is on wealth creation. There is no need to equate a past earnings record with earning power. There is no a priori reason to view accounting earnings as the best indicator of earning power. Among other things, the amount of resources in the business at a given moment may be as good or a better indicator of earning power.

Graham & Dodd also put down their thoughts about earning power, for instance in Security Analysis (quotation below from the sixth edition) in which they wrote:

Intrinsic Value vs. Price. From the foregoing examples it will be seen that the work of the securities analyst is not without concrete results of considerable practical value, and that it is applicable to a wide variety of situations. In all of these instances he appears to be concerned with the intrinsic value of the security and more particularly with the discovery of discrepancies between the intrinsic value and the market price. We must recognize, however, that intrinsic value is an elusive concept. In general terms it is understood to be that value which is justified by the facts, e.g., the assets, earnings, dividends, definite prospects, as distinct, let us say, from market quotations established by artificial manipulation or distorted by psychological excesses. But it is a great mistake to imagine that intrinsic value is as definite and as determinable as is the market price. Some time ago intrinsic value (in the case of a common stock) was thought to be about the same thing as “book value,” i.e., it was equal to the net assets of the business, fairly priced. This view of intrinsic value was quite definite, but it proved almost worthless as a practical matter because neither the average earnings nor the average market price evinced any tendency to be governed by the book value.

Intrinsic Value and “Earning Power.” Hence this idea was superseded by a newer view, viz., that the intrinsic value of a business was determined by its earning power. But the phrase “earning power” must imply a fairly confident expectation of certain future results. It is not sufficient to know what the past earnings have averaged, or even that they disclose a definite line of growth or decline. There must be plausible grounds for believing that this average or this trend is a dependable guide to the future. Experience has shown only too forcibly that in many instances this is far from true. This means that the concept of “earning power,” expressed as a definite figure, and the derived concept of intrinsic value, as something equally definite and ascertainable, cannot be safely accepted as a general premise of security analysis.

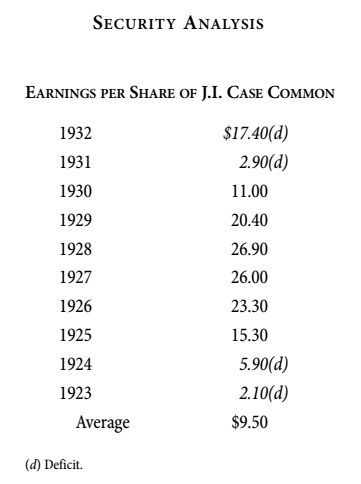

Example: To make this reasoning clearer, let us consider a concrete and typical example. What would we mean by the intrinsic value of J. I. Case Company common, as analyzed, say, early in 1933? The market price was $30; the asset value per share was $176; no dividend was being paid; the average earnings for ten years had been $9.50 per share; the results for 1932 had shown a deficit of $17 per share. If we followed a customary method of appraisal, we might take the average earnings per share of common for ten years, multiply this average by ten, and arrive at an intrinsic value of $95. But let us examine the individual figures which make up this ten-year average. They are as shown in the table on page 66. The average of $9.50 is obviously nothing more than an arithmetical resultant from ten unrelated figures. It can hardly be urged that this average is in any way representative of typical conditions in the past or representative of what may be expected in the future. Hence any figure of “real” or intrinsic value derived from this average must be characterized as equally accidental or artificial.

To get this kind of information and other exclusive articles before regular readers, get on the VIP Mailing List today.