Hindenburg vs. Adani: Caveats for Inspired Short-Sellers in Malaysia

Neoh Jia En

Publish date: Fri, 10 Feb 2023, 04:24 PM

- In the US, the claimant in defamation suits related to public matters has to prove that the defendant’s allegation is false; whereas in Malaysia, the burden of proof lies with the defendant.

- Malaysian short-sellers should hence exercise caution in publishing their allegations, unless they are confident of convincing the court that those allegations are true.

- Distinguishing opinions from facts is also critical since Malaysian laws protect the expression of fact-based opinions on public matters that are made fairly, but Hindenburg’s report on Adani Group might not be a good reference for this matter.

The recent showdown between Hindenburg Research (Hindenburg) and Adani Group has undoubtedly been an interesting episode and came along with a free publicity for Malaysia. Likely inspired by the impact of Hindenburg’s report, one of my friends has asked for my opinion about the prospect of publishing such reports while taking short positions via futures or structured warrants in Malaysia.

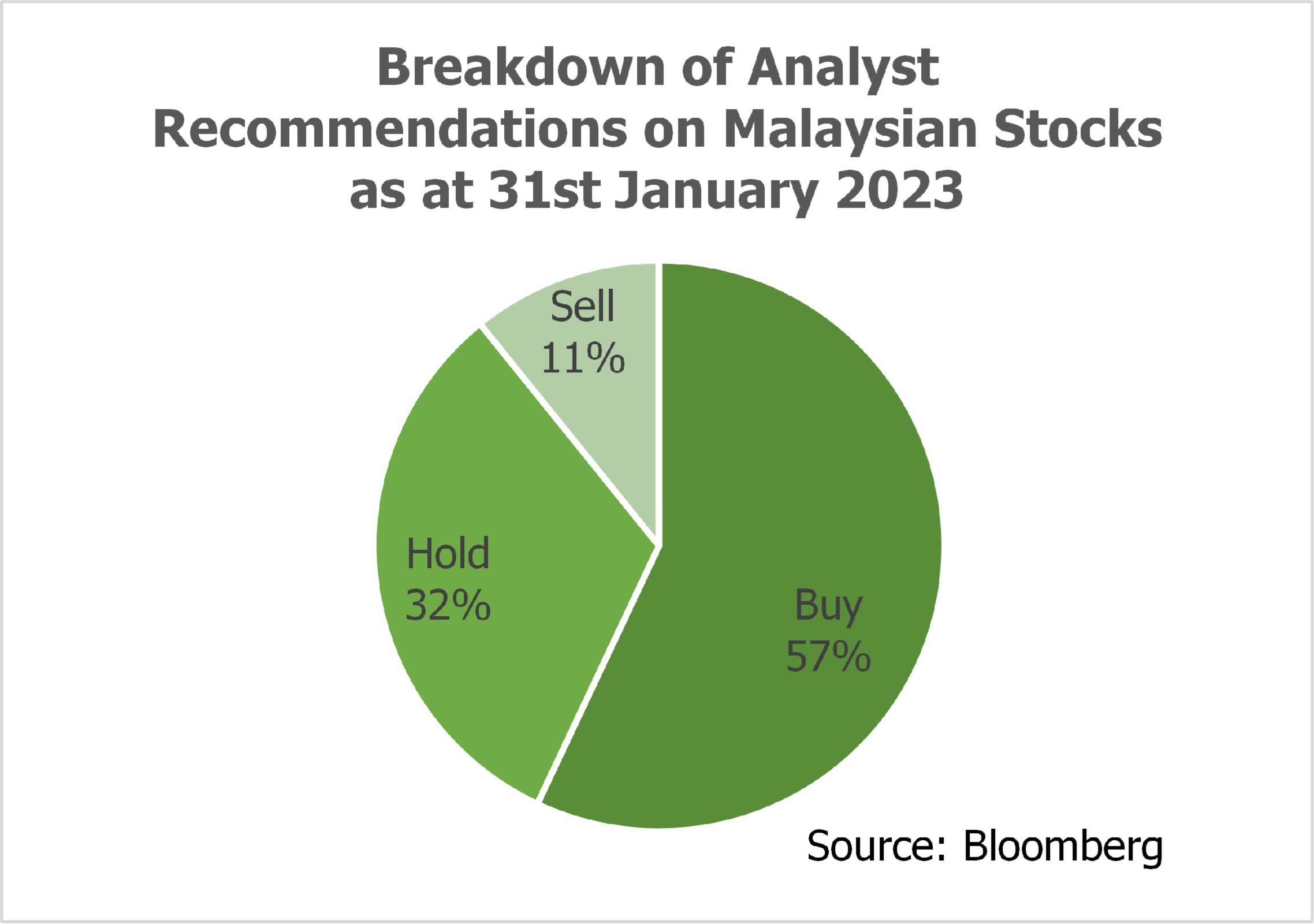

While I have my reservations about emulating the writing style of Hindenburg, I would look forward to a proliferation of bearish reports on Malaysian companies inspired by this episode between Hindenburg and Adani Group, if it ever materialised. A break in the monotonicity of analyst reports on Malaysian-listed stocks is much welcomed, where sell calls account for only 10.8% of all 1,898 active recommendations compiled by Bloomberg as at 31st January 2023; brokerage analysts usually do not bother writing about stocks that they are bearish on when most of their clients are long-only funds.

Laws on defamation in Malaysia

Of course, publishing reports that refer to and damage the reputation of any entity carries the risk of defamation lawsuits, and this is likely the issue that Malaysian short sellers are most concerned about. If truth is mispresented, the defamed entity may sue the publisher for civil damages under Defamation Act 1957 (civil defamation), and/or report to the police to have the publisher charged under Section 499 of the Penal Code (criminal defamation). Publishers have faced claims of up to ten of millions ringgit in civil defamation suits, and they may also be jailed for up to two years and/or be fined if convicted under defamation charges. This is made worse by the fact that separate charges may be made with respect to a single publication, depending on the number of mispresented facts or malice opinions contained in the publication.

Nonetheless, it is a common knowledge in Malaysia that one needs not to worry about defamation suits if he/she could prove that his/her allegation related to public matter is true. This defence of “justification” is provided in Section 8 of Defamation Act 1957 and in the First Exception to Section 499 of the Penal Code. Still, as mentioned by the judge in the 2014 case of Dato' Seri Mohammad Nizar bin Jamaluddin v. Sistem Televisyen Malaysia Bhd & Anor, the defendant must prove the truth “on the balance of probabilities, that is, the allegation is more likely than not to be true,” and this is a tall task in many cases.

Assessing potential justifications by Hindenburg

“Since the burden of proving the truth of an allegation is on the defendant, claimants [the defamed] enjoy a distinct advantage in defamation claims… It can often be difficult to obtain sufficient admissible evidence to persuade the judge that the statement is true. This will sometimes result in the media being unable to publish allegations which are generally believed to be true, but which they may not be able to prove to the standard required in court.”

~ Abang Iskandar Abang Hashim JCA, 2014

To illustrate the difficulty in raising a defence of justification in Malaysia, let’s assume that both Hindenburg and Adani Group are based in Malaysia, and that Hindenburg has presented its allegations as facts and has no further evidence other than those in its two reports published in January 2023. The question is whether Hindenburg can persuade the judge that all its allegations are true.

Examining allegations made by Hindenburg, it could be seen that most “evidences” quoted are corporate-governance issues which, while highly relevant for investors, are far from sufficient for a defence of justification in the court. Other than allegations involving dealings by the brother of Adani Group’s founder, for which there are clear rules that mandate disclosure as related-party transactions, and allegations that are restatements of investigation reports by authorities, Hindenburg’s allegations are mostly backed up by multiple loosely- connected facts, general statements and opinions of interviewees, or past cases that shed a negative light on the characters of alleged perpetrators – the latter two are either inadmissible or have extremely limited relevance in the court as per the Evidence Act 1950. These could be seen for example in both allegations of stock manipulations by Adani Group.

In claiming that Adani Group has manipulated its listed entities’ stocks via offshore funds, Hindenburg attempts to show the relationship between Adani Group and four offshore funds and that those funds account for relatively high proportions of trades done on Adani Group’s listed stocks. Evidences quoted include: (1) those funds’ highly concentrated investments in Adani Group-related stocks; (2) opinions of ex-employees of those funds and traders; (3) the tie with Adani Group via for example, the use of a common corporate service provider or that the fund management company’s CEO had served on the same board of some unrelated companies as the father-in-law of the niece of Adani Group’s founder did; (4) a related party of Adani Group invested USD 17m in one of the fund; and (5) those funds collectively accounted for up to 47% of annual institutional fund flows into/out of Adani Group’s listed stocks. Most of these “symptoms” have alternative explanations, for example funds’ unique strategy, biased opinions, or just coincidences; even the seemingly relevant investment by a related party of Adani Group may be inconsequential at all since there is no mention about the source of the USD 17m and its relative size.

Hindenburg’s case for Adani Group’s stock manipulation practices due to the group’s ties to known stock manipulators is (un)fortunately even less convincing. While it is undeniable that Adani Group was involved in and prosecuted due to a stock manipulation case in 1999-2001, such a character evidence, if ever admitted by the court against an artificial person, is a "very weak" one. More irrelevant are the facts that Adani Group’s stocks were manipulated in 2003 and in 2004-05, for which Hindenburg admits that there was no mention by the regulator about any involvement of Adani Group and yet writes about them. Other “ties” supported by opinions of traders, or by the fact that a private company of the brother of Adani Group’s founder has utilised the service of a brokerage allegedly owned by an associate of a convicted market manipulator, are also seemingly too far-fetched.

Right to reputation vs. right to free speech

“American constitutional law is distinguished by its protection of defamers, rather than the defamed.”

Given uncertainties in relying on other defences against defamation and that Hindenburg is likely not able to provide solid evidences for all its allegations, I was surprised by the research firm’s move to challenge Adani Group to file suit in the US. A wiser move would have been keeping quiet while hoping that Adani Group crumble under investigations by authorities or under the market force such that it does not have time to react. The research firm’s statement that “we have a long list of documents we would demand in a legal discovery process,” however, suggests that the burden of proving falsity lies with Adani Group should it file a defamation case in the US – and this is indeed an overriding factor.

Unlike in Malaysia, the claimant of a defamation case, whether criminal or civil, concerning public matter in the US has to prove that the defendant’s allegation is false. This difference stems from the US Constitution that provides for the right to free speech but not the right to reputation, and was established by the US Supreme Court in the seminal case of New York Times v. Sullivan in 1964 while noting that “erroneous statement is inevitable in free debate.” Whereas Article 10 of the Federal Constitution of Malaysia, much like Article 19 of the Constitution of India, provides a better balance between the right to free speech and the right to reputation.

Since proving non-existence is much more difficult than proving existence, claimants of defamation cases in the US may find it impossible to establish their cases, or as Prof. Franklin and Prof. Bussel put it, “a wide range of statements that cannot be proved either true or false necessarily are absolutely protected.” An example in the case of Adani Group is proving that the group has no relationship with the aforementioned offshore funds; any attempt by Adani Group to reveal those funds’ investors and source of funds would require cooperation from third parties, assuming that they are independent. This is not to mention that any defamed public figure in the US has to further show that the defendant acted with malice, which is a demanding requirement added by the US Supreme Court since the aforementioned case of New York Times v. Sullivan.

In light of legal challenges in the US, Adani Group should benefit from a signalling effect should it go out of its way to institute a defamation suit in the country. Of course, the group’s default route, which it has pursued multiple times in the past, is to file a criminal defamation suit in India (under Section 499 of the Indian Penal Code which is identical to Section 499 of the Malaysian Penal Code) and hope that the government of India would charge Hindenburg at taxpayers’ expense. If this is the case, it would help in explaining the group’s non-sensical reply that the research firm’s report is “a calculated attack on India.”

Facts vs. Opinions

In any case, Malaysian short-sellers that target Malaysian companies should be aware that emulating Hindenburg, or any other US short-seller, might not be a great idea unless they could confidently prove their allegations in the court. Fortunately, opinions on public matters are allowed as free speech in Malaysia, much like the case in the US, but short-sellers must present them carefully to establish a defence of fair comment in case of receiving any defamation suit.

As provided in Section 9 of Defamation Act 1957 and in the Third, Fifth and Tenth Exception of Penal Code, and upheld by the Malaysian court in the 1989 case of Joshua Benjamin Jeyaretnam v Goh Chok Tong, a defence of fair comment could be established if all of the following conditions are met: (1) the words complained of are in the form of comment; (2) the comment is on a public matter; (3) the comment is fact-based; and (4) the comment is fair. Hence, short-sellers should have ample room to voice their opinions on matters related to publicly-listed companies in Malaysia, although the few reports that I have sighted so far have failed to even distinguish between facts and opinions which is the very first requirement to establish a defence of fair comment – and which is also a legal advice disguised as standard of practice by the CFA Institute to its members who are mostly investment professionals.

Furthermore, while Hindenburg has presented its reports as opinion pieces and has successfully raised the defence of fair comments in the past, Malaysian short-sellers should think twice before writing as assertively as the research firm does, due to the difficulty in relying on the defence of justification in Malaysia and also the subjective interpretation of a “fair comment,” which as per Joshua Benjamin Jeyaretnam v Goh Chok Tong, is one that a fair-minded person could have honestly made based on available facts. Allegations like “Taken together, these facts paint a blindingly obvious picture to us – PMC Projects is an Adani Group private entity used to suck money out of the Adani Group’s publicly listed entities with no disclosure of the conflict to investors” or “Although SEBI’s investigation has not reached a logical conclusion, ours has” would likely challenge the boundary of defamation law in Malaysia.

All in all, Malaysian short-sellers should adopt a more neutral tone on their opinions while ensuring that facts referred to are verifiable, should they wish to minimise legal risk to their publication. A good way of learning to do so is by reading academic journals, in which strong positive language is rarely used (for example, “we do not reject the null hypothesis” rather than “we accept the null hypothesis”) and references are cited to help readers in locating source materials. Fortunately, the proliferation of open-access journals has made many of these papers available for free online, and there is little reason why anyone could not learn to write neutrally.

More articles on Lorem ipsum

Created by Neoh Jia En | Feb 02, 2024

Created by Neoh Jia En | May 29, 2023

Created by Neoh Jia En | Dec 30, 2022