Has Yinson Found the Yellow Brick Road? Part 3: In SC We Trust

Neoh Jia En

Publish date: Thu, 17 Feb 2022, 09:30 AM

- Earnings per share (EPS) is not for illustrative purpose only, as its computation is standardised by IFRS and MFRS.

- IAS 1’s/MFRS 101’s concept of “fair presentation” and IAS 33’s/MFRS 133’s requirement to separately compute EPS for each class of shares that has different profit entitlement further support the need to exclude distributions to perpetual bond holders from EPS computed for ordinary shareholders.

- Mistakes in financial statements may expose directors and auditors to legal consequences.

- Yinson should be in a better position to understand financial reporting requirements set by the Securities Commission given that its audit committee is being headed by a board member of the regulator.

Few hours after posting my initial writeup, a stakeholder of Yinson Holdings Berhad (Yinson) contacted me to discuss the issue. They conceded that the financing cost for equity-classified perpetual bonds is higher than that for traditional borrowings due to the higher risk of deferred payments borne by those securities holders. However, there is a good reason for funding via perpetual bonds.

Floating production storage and offloading (FPSO) unit projects are typically funded with 70-80% debt and 20-30% equity. Due to the stable cash flows generated by FPSOs and ring-fencing practices (lenders to individual projects typically have first claims on the project’s assets), Yinson has faced no issue in securing project debt financing. However, the need to fund project equities has grown much faster than Yinson’s internally-generated cash flows, in light of the structural demand for and of the shortage of FPSOs globally. With some FPSO projects, for example FPSO JAK and FPSO Marlim-2, requiring over RM1 billion in financing, Yinson had to raise equity financing to undertake those profitable projects.

Although the usual way for equity financing is to issue ordinary shares, Yinson’s capital recycling strategy might have made this new capital redundant after a few years if there is no new project opportunity.

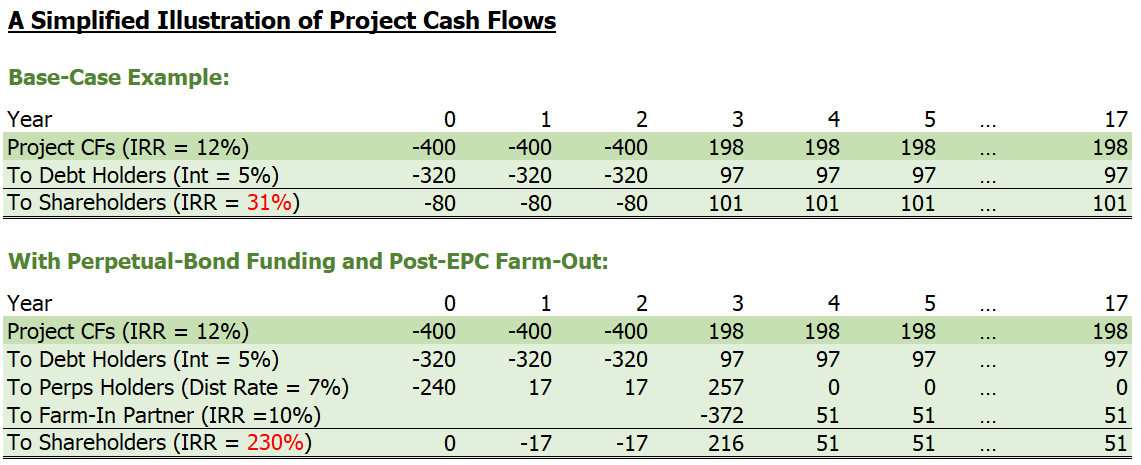

In particular, the execution risk and expertise required for FPSO projects are the highest during their engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) phase in the initial two to three years, hence potential investors would require a lower return after those projects have been accepted by clients. Amidst the tight supply of FPSOs, it is possible for Yinson to achieve internal rate of returns (IRR) of over 20% for some of its projects (according to analyst reports, this might be the case for FPSO Abigail-Joseph and FPSO Atlanta). As an illustration, should Yinson farm out stakes in these projects post-EPC at the price where new investors receive IRR of 10%, the group could double its initial capital invested and “recycle” these money to new projects where IRR exceeds 10%. By deploying its capital mainly to the most profitable phase of FPSO projects, Yinson could maintain its high return on equity.

Hence, for each FPSO project, equity financing may be required for only three to five years. Had Yinson issued ordinary shares, there might be undeployed capital post farm-out. Redeemable perpetual bonds suit the group’s equity financing needs better, since Yinson could just repurchase them after selling stakes in FPSO projects.

Besides its bona fide rationale for utilising perpetual bonds, Yinson also lack the intention to mislead investors via EPS, since there is no institutional investor who values the group’s equity by price-to-earnings ratio. All seven research houses that I managed to track utilise discounted cash flows method to value Yinson. This is reasonable since discounted cash flows method is preferred when valuing businesses with stable cash flows.

However, is there a case for unintentional miscalculation of EPS? My meeting with the said stakeholder ended without a conclusion since they had to check with their accountants and auditors.

Can EPS Be a Subjective Measure?

Two weeks later, a suggestion emerged: Yinson has discretion on paying dividends to ordinary shareholders and distributions to perpetual bond holders, hence EPS is a purely “indicative” measure.

However, the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) and Malaysian Financial Reporting Standards (MFRS) standardise the computation of EPS for publicly-listed companies. Paragraph 2 of IAS 33/MFRS 133 states that the standard applies to the consolidated and individual financial statements of companies whose shares are publicly traded or in the process for an initial public offering. Paragraph 3 emphasises that “An entity that discloses earnings per share shall calculate and disclose earnings per share in accordance with this Standard.”

While companies could disclose additional EPS measures that do not conform with IFRS/MFRS in their financial statements (the International Accounting Standards Board has sought opinions on this matter in its discussion paper on principles on disclosure issued in March 2017, and has decided not to develop any requirement on such practices), those non-IFRS/non-GAAP measures should be presented in a way that “sufficiently and clearly differentiates” them from the financial statement, as provided by paragraph 53 of International Standard on Auditing 700.

It is hence clear that EPSs disclosed in financial statements, when a departure from IAS 33/MFRS 133 has not been specified, should be based on definitions and methods prescribed by IFRS/MFRS, and my question regarding the compliance of EPS computation method chosen by Yinson, Malakoff Corporation Berhad (Malakoff), PESTECH International Berhad (PESTECH), and Dialog Group Berhad (Dialog) remains valid.

The Little Things That Matter

Despite the irrelevance of EPS measure to institutional investors of Yinson, and most likely of Malakoff and Dialog as well, unspecified non-compliance with IAS 33/MFRS 133 that governs EPS computation may still have serious legal consequences.

In Malaysia, financial statements of publicly-listed non-foreign companies are required to comply with MFRSs as implied from Section 26C of Financial Reporting Act 1997, and also effectively with IFRSs as provided by paragraph MY16.1 of MFRS 101. These include quarterly financial statements which are governed by IAS 34/MFRS 134, which in turn refers (in paragraph 11) EPS computation to IAS 33/MFRS 133.

In “extremely rare circumstances” where compliance with MFRSs and IFRSs would not result in a “true and fair” view of the financial position or financial performance, management may choose to depart from these standards as provided by paragraph 19 of IAS 1/MFRS 101 and Section 244(3) of Companies Act 2016 (CA 2016). However, any departure must be disclosed and explained. All four companies in question have not indicated departure from IAS 33/MFRS 133.

The legal requirement for “true and fair” view, or IAS 1’s/MFRS 101’s concept of “fair presentation,” in fact compels management to provide disclosures beyond those that have been specified by IFRS/MFRS. One example lies in IAS 33’s/MFRS 133’s requirement for differentiation of profit attributable to different classes of equity owners: paragraph 66 of IAS 33/MFRS 133 calls for the computation of separate EPS for each class of shares that has different right to share in profit. Hence, ignoring distributions to equity-classified perpetual bonds in the computation of EPS, even though perpetual bonds have not been explicitly provided for in IAS 33/MFRS 133, may also result in non-compliance with IAS 1/MFRS 101.

As stated in Section 251 of CA 2016, the board of directors is in charge of approving financial statements, hence directors are most exposed to the risk of misstatements. Non-compliance in financial reporting may lead to a fine of up to RM500,000 and/or imprisonment of up to one year on every officer (includes directors as per definition in Section 2) who commits the offence.

The consequences of intentional misstatements are worse. Both Section 591-593 of CA 2016 and Section 369 of Capital Markets and Services Act 2007 (CMSA 2007) provide for false reporting, penalties for which include imprisonment of up to 10 years and a fine of up to RM3 million. The general wordings of these sections also make directors accountable for deliberate misstatements of information outside of financial statements, arguably including the disclosure of “Profit/(Loss) Attributable to Ordinary Equity Holders of the Parent” in the table of quarterly financial performance reported to Bursa Malaysia.

The Mouse Deer in Between

One feedback that I received is that EPS is considered “other information” disclosed in annual reports but outside of financial statements, for which auditors bear no ultimate responsibility. The source of misunderstanding appeared to have come from Appendix 1 of International Standard on Auditing 720, where EPS is given as an example of information in a summary of key financial results included in annual reports.

While EPS could be indeed be replicated, or even adjusted, and reported outside of financial statements, those are information voluntarily provided by the management. Doing so does not eliminate the need to disclose EPS in the statement of comprehensive income, or profit or loss, as provided in paragraph 66 of IAS 33/MFRS 133.

Unfortunately, auditors may also bear legal consequences for misstatements of EPS in audited annual financial statements, depending on the interpretation of “reasonable assurance” required from them as per paragraph 5 of International Standard on Auditing 200.

Section 266 of CA 2016 and Section 320 of CMSA 2007 spell out auditors’ duties to report non-compliance of financial statements to the relevant authorities. Penalties for failing to do so are specified in Section 266(13) of CA 2016: imprisonment of up to five years and/or a fine of up to RM3 million.

While financial statements are not guaranteed to be free from material mistakes, the key consideration of whether auditors are liable lies in whether they have sufficiently performed their duties in providing “reasonable assurance.” This is subjective and the relevant case law shall apply.

Regulator on Yinson's Board

One fact that investors could draw comfort from is that Yinson has managed to attract a board member of the Securities Commission (SC) to join the group’s board of directors.

As per Section 26D of Financial Reporting Act 1997, the SC is the relevant authority that provides specifications and guidelines on financial reporting by publicly-listed companies. Yinson is thus in a better position to understand requirements specified by the SC.

This advantage is amplified by the said independent board member’s position as the chairman of Yinson’s audit committee, which is responsible for reviewing financial statements before approval by the board, as stated in paragraph 15.12(1)(g) of Bursa Malaysia’s Listing Requirements.

Misstatements by Yinson should hence be extremely unlikely, when the group has a regulator on its board and was/is assigned the “most senior” auditors from two of the Big Four accounting firms. Likely, external auditors would be able to provide their rationales on allowing those companies’ method of computing EPS during the latter’s annual general meetings.

*This post is a follow-up to my previous posts titled "Has Yinson Found the Yellow Brick Road?" and "Has Yinson Found the Yellow Brick Road? Part 2: Common Misconceptions."

*For follow-ups, see my posts titled “Sunway Berhad – Part 2: Above the Rising Cloud” and "Has Yinson Found the Yellow Brick Road? Part 4: Homecoming."

Related Stocks

| Chart | Stock Name | Last | Change | Volume |

|---|

More articles on Lorem ipsum

Created by Neoh Jia En | Feb 02, 2024

Created by Neoh Jia En | May 29, 2023

Created by Neoh Jia En | Feb 10, 2023

Created by Neoh Jia En | Dec 30, 2022